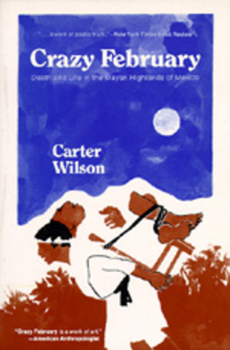

Crazy February: Death and Life in the Mayan Highlands of Mexico

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Products of the "imagination," such as novels, can be especially useful tools for understanding how things work in societies far removed from our own experience. Through the telling of a story, a sound ethnographic novel conveys more than information. It involves the reader in the dynamics of life in places where the rules for action are very different from the rules the reader makes his own decisions by. Some people believe ethnographic novels are comparable to fieldnotes- the data themselves in their original, unanalyzed form. Though I can see the reason for the analogy, the author still disagree with it. Good fieldnotes record raw experience. For the time being, the anthropologist squelches his desire to interpret, and he writes down everything he can see or remember. Good ethnographic fiction also presents experience raw, without generalization. But in building the story, in selecting to tell this because it is important and not to tell that because it seems trivial, the novelist is analyzing his material. Between the raw and the cooked, both ethnographies and ethnographic novels belong in the processed pot. Anthropologists try to make explicit and public both the method they have used to gather their material and the means for analyzing it. Ordinarily, a novelist obscures his analysis-the grounds for the choices he has made-and depends on the interior logic of the story to make his tale seem "true" or "believable." But Crazy February works with somewhat different principles than the author would normally use in writing "fiction." The book grew directly out of field experience. Wilson felt strongly that it would stand or fall on its ethnographic correctness. And so, faced with choices between what the author would like to see in the story and what he thought would actually happen to an Indian in the mountains of Chiapas, he consistently chose "actuality." In a practical, day-to-day writing sense, reality was the author's rod and my staff. And in the end he was very happy when anthropologists with greater experience in the Mayan area found the book essentially exact and, more important, true to the spirit of the place he had written about.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0520023994

ISBN13:9780520023994

Release Date:April 1974

Publisher:University of California Press

Length:264 Pages

Weight:0.65 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 5.3" x 7.9"

Customer Reviews

3 ratings

Highly recommended

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

This is a remarkably good book. Anyone interested in Mexico, Chiapas, indigenous cultures, or the Zapatista rebellion of 1994 in Chiapas should regard this as essential reading. Wilson gives, in a very readable fictional format, a clear and fascinating account of traditional life, culture, and values in a highland indigenous community. Those who read this should also see Wilson's ¨A Green Tree and a Dry Tree¨ about a rebellion fomented by this same Indian community in 1969, a real event but also presented in the form of a novel.

The Best Anthro Fiction

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Wilson's Crazy February is perhaps the best example of anthro fiction that I've read, and gives a much clearer idea of life in Chiapas than most anthro nonfiction. Crazy February gives the reader an acute sense of what it is really like to live there. I'd also recommend Peter Matthiessen's Far Tortuga as another wonderful example.

Indian life in Highland Chiapas

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

This is an excellent book. It captures the reality of life in an Indian village in Mexico during the 1950s and 1960s. The author spent considerable time in the highlands of Chiapas doing anthropological fieldwork, and his fictional work captures many of the aspects of ladino/Indian relations which continue to plague Mexico to this day. If you want a good, emotive background to the Zapatista rebellion, this is it! Also highly recommended: Wilson's fictional account of the Tzeltal uprising of the mid 18th century "A Green Tree and a Dry Tree"