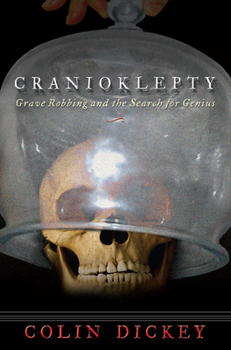

Cranioklepty

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The after-death stories of Franz Joseph Haydn, Ludwig Beethoven, Swedenborg, Sir Thomas Browne and many others have never before been told in such detail and vividness. Fully illustrated with some... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:1932961860

ISBN13:9781932961867

Release Date:September 2009

Publisher:Unbridled Books

Length:320 Pages

Weight:1.32 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 6.4" x 9.1"

Customer Reviews

2 ratings

A Fascinating Page-Turner!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

This book is very hard to put down. The pages turn by themselves as the author weaves captivating (and occasionally gory) tales of grave robbing, phrenology, craniometry and the post-mortem lives of certain skulls - that is, the skulls of certain deceased people who were recognized as geniuses. These include Haydn, Beethoven, and Mozart among several others. It was hoped that the study of such skulls would help identify physical characteristics indicative of high human intelligence. The word `cranioklepty', for the purposes of this book, essentially means the robbing of skulls/heads from coffins/crypts (usually). The time period covered is centered mainly in the nineteenth century; however, relevant matters that took place earlier are also discussed, as well as those up to and including the twenty-first century. The writing style is clear, friendly, lively, often witty, occasionally tongue-in-cheek, always captivating and widely accessible. This book should appeal to history buffs as well as anyone who likes a good well-written detective mystery.

Skulduggery

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

There is something simultaneously ghastly and funny about a human skull. A skull is an astonishing piece of sculpture, the most intricate of the bones in the body, but it always stands as a reminder that we are all mortal and mortality is temporary. It is mere happenstance that the skull of even the most disagreeable misanthropist seems to grin at us, but that classic spooky grin is just part of the reminder. There was a time, though, when skulls were more than _memento mori_: they were a window for information on the personality and a guide to the nature of genius itself. Since the skulls of geniuses were so informative, they were valuable, and since they were valuable, people stole them. That's the funny and ghoulish history in _Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius_ (Unbridled Books) by Colin Dickey. Dickey has written both fiction and nonfiction before, and anyone who picks up this book might be forgiven for thinking he is slipping in bizarre tales from his warped imagination. Nope - check the footnotes and the extensive references; they don't indicate an academic tome, but rather evidence for that trusty proposition of truth being stranger than fiction. The Enlightenment was a time of increased reliance on science, and one of its offshoots was phrenology, which wanted to be a science, and tried, but was revealed to be a pseudoscience only after long decades during which plenty of scientists believed in it. Franz Joseph Gall invented it in 1796, imagining that certain areas of brains handled certain skills, that swellings of a brain in a particular area meant a high degree of skill, and the skull would reflect such swellings. Gall and his followers liked collecting skulls to make their determinations, but they had a lot of skulls of criminals; they wanted skulls of geniuses. And they got them. Joseph Rosenbaum, for instance, was an accountant, music lover, and amateur phrenologist. He was a friend of Haydn, and had a unique way to show his respect for Haydn's genius. He stole his head. Shortly after Haydn's death in 1809, Rosenbaum bribed a gravedigger and got his trophy, which was stripped of flesh by accomplices at a local hospital, and then bleached in limewater. This caused some embarrassment in 1820 when Prince Esterhazy arranged to have Haydn's body moved to a more splendid grave: there was no head to the body, only a wig. The skull was meaningless scientifically but as a relic, it passed to the Society of Music in Vienna. The possession of the skull and what should be done with it and by whom were argued about for over a century before it was reburied in 1954. When Mozart died, a church sexton, realizing that the fate of the poor man was that he would be buried in an unmarked pauper's grave, put a wire around the composer's neck. A few years later he went back and dug around, finding his tagged prize. The rest of Mozart stayed in its unmarked grave, and so the skull, unlike that of Haydn, has nowhe