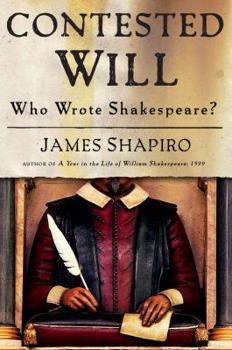

Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

For more than two hundred years after William Shakespeare's death, no one doubted that he had written hi plays.?Since then, however, dozens of candidates have been proposed for the authorship of what's generally agreed to be the finest body of work any playwrite in the English language. In this remarkable book, Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro explains when and why so many people began to question whether Shakespeare wrote his plays. Among the doubters have been such writers and thinkers as Sigmund Freud, Henry James Mark Twain, and Helen Keller It's a fascinating story, replete with forgeries, deception, false claimants ciphers and code, conspiracy theories-and a stunning failure to grasp the power of the imagination.AsContested Willmakes clear, much more than proper attribution of Shakespeare's plays is at stake in this authorship controversy. Underlying the arguments over whether Christopher Marlowe, Francis Bacon, or the Earl of Oxford wrote Shakespeare's plays are fundamental questions about literary genius specifically a out the relationship of life and art. Are the plays (and poems) of Shakespeare a sort of hidden autobiography? DoHamlet , Macbeth ,and the other great plays somehow reveal who wrote them?Shapiro is the first Shakespeare scholar to examine the authorship controversy and its history in this way, explaining what it means, why it matters, and how it has persisted despite abundant evidence that William Shakespeare of Stratford wrote the plays attributed to him. This is a brilliant historical investigation that will delight anyone interested in Shakespeare and the literary imagination.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:1416541624

ISBN13:9781416541622

Release Date:April 2010

Publisher:Simon & Schuster

Length:352 Pages

Weight:1.42 lbs.

Dimensions:9.3" x 1.0" x 6.3"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

A Brilliant Book That Won't Do Much Good

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

There's a good deal of evidence that William Shakespeare wrote the plays and poems attributed to him, and not a whit of evidence that any of the other people put forward as authors wrote those works. James Shapiro documents this nicely, and rips the "arguments" of the Baconians, Oxfordians, and defenders of other to shreds. None of which will actually convince those who believe someone else wrote Shakespeare's works. For, as Shapiro shows, and as the negative reviews demonstrate, the people who doubt "the man from Stratford" was the author start out with certain assumptions about the author of the plays and poems that make it impossible for said author to be William Shakespeare, son of John Shakespeare the glover. Why, don't you know that everyone who writes "fiction" is really writing autobiography? That's how we know Stephanie Meyer Twilight (The Twilight Saga) is really a teenager in love with a vampire, that David Weber On Basilisk Station (Honor Harrington) is genetically engineered female starship captain who looks like she's in her twenties as she pushes seventy (and has a six-legged telepathic cat for her best friend), that Arthur Koestler Darkness at Noon: A Novel was a Russian Revolutionary shot in the back of the head by Stalin before WWII, but who somehow wrote a book about his execution after his death. So the author of the A Midsummer Night's Dream,A Midsummer Night's Dream was obviously an aristocrat, a supernatural being, a lovelorn young woman, and an actor from the lower classes. Quite a feat, to be all of these at once. The author of Romeo & Juliet, Romeo and Juliet (Folger Shakespeare Library), West Side Story (Special Edition Collector's Set) was a young man who was also a woman who fought duels, was killed in one, and committed suicide twice, and was successful both times. And the author of Macbeth (The Annotated Shakespeare), was a cynical traitor, usurper, and murderer who consorted with witches. Boy, are we fortunate he got away with his crimes long enough to write those plays. And I am Marie of Romania The Portable Dorothy Parker (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition). If, however, you're not a fool, you'll find out a good deal from this book about William Shakespeare, the greatest playwright in the history of English literature, the biographers who make up bullstuff concerning him, and the loonies who can't conceive that someone, somewhere, might actually have an imagination capable of making stuff up. Quite enjoyable, and important.

Fascinating insights into why we question authorship

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

I expected yet another screed supporting one candidate or another in the Shakespeare authorship debate, but this fascinating book (while endorsing the man from Stratford as the author, or at least one of the authors, of the plays) takes us on a slightly different journey, exploring the history of the debate in the context of authorship challenges in general. Professor Shapiro's extensive research relates the arguments about Shakespeare's plays to the arguments about the authorship of Homer and of the Bible itself. We learn a lot about critical thinking over the centuries and about how our current literary expectations color our concepts of authorship. Easy and fun to read, like his earlier 1599, this is an important book for anyone who asks about authorship because it challenges us to explore why we are asking the question and what preconceptions we bring to the inquiry.

watch the agendas

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

It should be obvious that the low-star reviews on this masterful book are by people who disagree with Shapiro's conclusion that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare. These critics are not rating the book; they are rating Shapiro's adherence to their views, and they find him wanting. They should actually be rating the book higher, since this book is the most sympathetic and serious analysis of their views they are likely ever to receive from a legitimate scholar who does not agree with them. After you've looked at both sides of this argument carefully, your likely decision will come down to these questions: Do you believe that historical documents usually refer to actual historic events, or are they essentially untrustworthy and were created to hide secrets for which there is no direct documentation? Do you believe that creative writers can imagine things they haven't lived and also that they can do research to find out facts they can use in their creations, or do you believe that creative writers are essentially dressing up their autobiographies for whatever reason and cannot write about anything they have not directly experienced? That pretty much sums it up, because if you don't believe in hundreds of written documents, and you don't believe in imagination, you can't believe in Shakespeare. Or Stephen King for that matter, who is, as the perceptive readers all know, a front for the Queen of England's autobiographical writings.

New angle on a well-worn topic

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Thank God this is not another tiresome he-said she-said series of assertions and rebuttals that never changes anybody's opinion. If you only want to read one book about the Shakespeare authorship madness, make this one it. Shapiro gets to the heart of why anti-Stratfordism began in the first place: Shakespeare had been elevated to the status of a secular God, causing 18th and 19th century readers to wonder about what sort of man he was. Neither biography nor the cult of celebrity had been invented in Shakespeare's time, so nobody thought to interview him or his family and co-workers until they were long dead (not unusual at all; we know hardly anything about other playwrights such as John Webster, Thomas Kyd, George Chapman, Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher, or Thomas Dekker, because they, like Shakespeare, were never in serious trouble with the law or attracted the attention of the authorities the way Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson did). Couple the obscurity of his biography with the romantic idea that all art is self-expression and all literature is autobiography, let it brew in an atmosphere of religious and societal skepticism, and pretty soon someone was bound to come up with the idea that the life of Shakespeare, like that of Jesus and Homer, owed more to mythology than fact. Shapiro explains this very well and in a manner that anybody can follow. I don't understand the reviewer who complained that the style is dry: his wit, yes; his style, no. As for evidence for Shakespeare, it's the same as for any other writer of the period: title pages, government records (such as the Stationers' Register that licensed all books before they were printed), and contemporary testimony from people who knew him. Evidence for all others? Since there's zero of the type used by literary scholars, their proponents are forced to try to sift biographical information from the plays and poems (a method that has so far identified more than 60 Elizabethans as the "true" author, an indication of its reliability), to compare parallel passages from Shakespeare and the writings of others (Bacon and Marlowe), and to find and decode hidden messages embedded in Shakespeare's works or other works written about him (almost all of the alternative candidates). Hopefully this book will cause other academics to engage anti-Stratfordians instead of simply ignoring them and hoping they'll go away. Although like the poor, anti-Stratfordians will always be with us (like alien abductionists or DaVinci coders), more books like Shapiro's are needed to understand the historical forces that help shape such reality-denying fringe theories.

Why Some Think It Wasn't Shakespeare

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

I can't remember, but I think it was Woody Allen who wrote the joke: The plays of William Shakespeare were not written by Shakespeare himself, but by someone with the same name. The only reason the joke works is that for a couple of centuries there have been skeptics who have denied that Shakespeare's works were actually the works of Shakespeare. In _Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?_ (Simon and Schuster), it's not a surprise that James Shapiro answers the question in the subtitle the way he does: Shakespeare did. After all, Shapiro is a Shakespeare scholar whose most recent book was a look at one year (1599) in Shakespeare's life and how the plays he was writing were formed by the political and social environment of that time. So, yes, "He would say that, wouldn't he?" will be the response from the current skeptics, all of whom have their own candidate for the position of Bard. Shapiro's book, indeed, puts an unassailable case for Shakespeare of Stratford being the author, but that is only at the end. Everything that goes before is a history of the anti-Stratfordian movement. It is a wonderfully clear explanation of why skeptics started going wrong and have continued vehemently on their wrong paths. It is an entertaining and often hilarious tale, a path strewn, as Shapiro says, with "fabricated documents, embellished lives, concealed identity, pseudonymous authorship, contested evidence, bald-faced deception, and a failure to grasp what could not be imagined." There is no evidence that anyone in Shakespeare's time thought that the plays came from anyone else. In fact, it was only a couple of centuries after his death that doubters started piping up. It was a response to a lack of knowledge about the man himself; we don't have his letters or a journal, so why not simply read the poems and plays to get glimpses of biography? This was in harmony with the philosophy of the Romantics. The cases against Shakespeare started with Delia Bacon, an American intellectual and lecturer who picked Francis Bacon (no relation), who may have been a polymath but whose output shows no evidence that he could write plays and poems. The idea of Bacon's authorship was taken seriously by many, including Mark Twain, who won over his friend Helen Keller into the Baconian camp. The most popular counterproposal to Bacon is Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford. A schoolmaster named J. T. Looney (whose name has caused titters to non-skeptics ever since) proposed that the plays had so many details of such things as legal lore, falconry, and foreign travel that a mere actor from Stratford could not have written them. Oxford, however, knew plenty about such things, and had three daughters (just like King Lear!) and his wife married at thirteen (just like Juliette!). Looney made many converts, chief among them being Sigmund Freud, whose advocacy of Oxford got in the way of friendships and of the psychoanalysis of at least one patient who would not come a