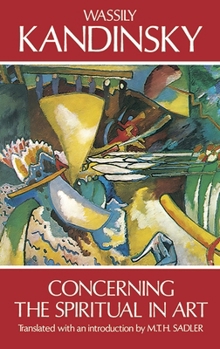

Concerning the Spiritual in Art

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

A pioneering work in the movement to free art from its traditional bonds to material reality, this book is one of the most important documents in the history of modern art. Written by the famous nonobjective painter Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), it explains Kandinsky's own theory of painting and crystallizes the ideas that were influencing many other modern artists of the period. Along with his own groundbreaking paintings, this book had a tremendous impact on the development of modern art.

Kandinsky's ideas are presented in two parts. The first part, called "About General Aesthetic," issues a call for a spiritual revolution in painting that will let artists express their own inner lives in abstract, non-material terms. Just as musicians do not depend upon the material world for their music, so artists should not have to depend upon the material world for their art. In the second part, "About Painting," Kandinsky discusses the psychology of colors, the language of form and color, and the responsibilities of the artist. An Introduction by the translator, Michael T. H. Sadler, offers additional explanation of Kandinsky's art and theories, while a new Preface by Richard Stratton discusses Kandinsky's career as a whole and the impact of the book. Making the book even more valuable are nine woodcuts by Kandinsky himself that appear at the chapter headings.

This English translation of ber das Geistige in der Kunst was a significant contribution to the understanding of nonobjectivism in art. It continues to be a stimulating and necessary reading experience for every artist, art student, and art patron concerned with the direction of 20th-century painting.