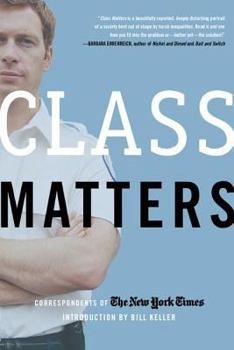

Class Matters

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The acclaimed New York Times series on social class in America--and its implications for the way we live our lives

We Americans have long thought of ourselves as unburdened by class distinctions. We have no hereditary aristocracy or landed gentry, and even the poorest among us feel that they can become rich through education, hard work, or sheer gumption. And yet social class remains a powerful force in American life. In Class Matters, a team of New York Times reporters explores the ways in which class--defined as a combination of income, education, wealth, and occupation--influences destiny in a society that likes to think of itself as a land of opportunity. We meet individuals in Kentucky and Chicago who have used education to lift themselves out of poverty and others in Virginia and Washington whose lack of education holds them back. We meet an upper-middle-class family in Georgia who moves to a different town every few years, and the newly rich in Nantucket whose mega-mansions have driven out the longstanding residents. And we see how class disparities manifest themselves at the doctor's office and at the marriage altar. For anyone concerned about the future of the American dream, Class Matters is truly essential reading. Class Matters is a beautifully reported, deeply disturbing, portrait of a society bent out of shape by harsh inequalities. Read it and see how you fit into the problem or--better yet--the solution!--Barbara Ehrenreich, author of Nickel and Dimed and Bait and Switch

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0805080554

ISBN13:9780805080551

Release Date:September 2005

Publisher:St. Martins Press-3PL

Length:288 Pages

Weight:0.62 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.5" x 8.2"

Customer Reviews

6 ratings

Confirmation of Proverbs 22-7

Published by RadioFan , 1 month ago

Namaste: I have only read the reviews and have not acquired the book, at least yet. The (meaningful) reviews, not discussing shipping/delivery, confirm the eternal truth of Proverbs 22-7. Just the context might have changed but I doubt even that.

Perfect..NEW

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

I bought this book expecting a nice, used book. To my suprise, it was brand new!!! I doubt it had ever been opened until I opened it. It got here within a week, and in EXCELLENT condition!!

Very insightful

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

I really liked this book. It really gave me a new perspective on viewing class and wealth in a way that I hadn't thought of before. I wasn't aware that there was still such a distinction between "old money" and "new money". I really found the book easy to read with a lot of interesting information. I would recommend this book to everyone.

We are not a classless society

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

I read two of the articles in this book when they originally came out in the NY Times and I'm glad they are out in a book form so that they can be read by everyone. The sociologist James Loewen in his book, Lies My Teacher Taught Me, said that the way history is taught in American high schools makes us "stupider" about social class because the subject is entirely avoided. Many Americans think we live in a classless society, one big, happy middle class, though the contrary is true (look how suburban subdivisions are divided by house prices, even on signs: the 300-399K development, the 499 and up, the 899K and up, the 100-159 "starter homes", and so on). A strength of this book for the general reading public is that it approaches class divisions in a number of different ways (healthcare, education, etc) by examining the lives of real people. This is a sociology text that uses concrete instances to elucidate general themes. When I attended Haverford College in the late 1970s and early 1980s after having grown up in a poor, working class neighborhood, I was struck by encountering people who were far more urbane, well-traveled, well-spoken, and well-dressed than I was. It was intimidating, but I learned to be a member of this world (I chuckle now at how kids made fun of my "accent" and corrected my grammar while I was speaking to them) and for the rest of my life I've been going between worlds, conscious of how I speak and act in each (I've "escaped" the social class I grew up in). Because of these experiences this book really resonates with me and I'm sure it will resonate with people who have had similar experiences. For everyone else, it is a welcome introduction to what we Americans are "stupid" about: social stratification in American society and how it determines our behavior, our opportunities, and our health.

Everyone should read this

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

If you're like me and you live in a community that is pretty much isolated from truly interacting with the lower-classes in any meaningful way, this book is educative to the extreme. It takes truths that we know about, but haven't experienced ourselves, like not having health insurance or living in modern-day tenament housing, and allows the reader to examine the social and cultural forces that allow this to exist. I had read the series when they were published in the NY Times last summer, but reading it in one compilation packs a punch. Anyone that says we live in a class-less society should have their eyes opened with this book.

An Eye Opening Account of Class Issues in America

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Most books about race and class in America tend toward the macroscopic, marshalling their arguments behind surveys, statistics, and broad statements of theory or conjecture. Case studies or anecdotes about specific individuals are presented, if at all, to illustrate and particularize from whatever generalized conclusions their authors happen to be espousing. Such works of course serve useful purposes, but they can seem coldly impersonal, lacking any sense of the human lives that comprise all those statistics. Only occasionally do writers like Studs Terkel or Barbara Ehrenreich come along to put a human face on these issues. Journalism, on the other hand, revels in the particular. Human drama provides the attraction, and individual stories create the base from which to propel the writer into broader statements of issues and positions. Thus, it is hardly surprising that CLASS MATTERS, a book compiled from stories previously published about class in America by the New York Times, should consist largely of anecdotes. That it works so well is a tribute not just to the writers themselves, but to the editorial framers of this collection. CLASS MATTERS addresses the great taboo of America, the myth of a classless society. Never does the book claim that American life is caste-bound or separated into rigid classes. Rather, the opening chapter asserts that while class mobility still exists (that is, one can be born poor and lower class but, through dint of steady self-application in school and hard work thereafter, the opportunities for "upgrading" oneself are effectively limitless), the degree of such mobility has lessened considerably in the last 30 years. Never has it been more true that the best choice one can make in life is one's choice of parents, and economic trends and (especially) Republican public policy are only exacerbating the problem. The bulk of CLASS MATTERS is taken up with extended newspaper articles that articulate various aspects of class in America and its effect on people's lives. For example, the opening chapter details the crises of three individuals who suffered heart attacks - how their responses, emergency care, choice of doctors and treatments, and follow-up care differed according to their socioeconomic class. Other stories document interclass marriages (she upper, he lower), a lawyer whose return to her Appalachian roots forces her confront class differences, an immigrant Mexican restaurant worker in New York struggling to survive while working for a successful, Greek immigrant boss, and an upward-striving family of corporate nomads bouncing from one big city bedroom community (like Alpharetta, Georgia) to another. CLASS MATTERS occasionally detours (to its positive credit) away from pure case history reporting to discuss more general topics. One of the most telling concerns the dropout rate in American four-year colleges (only 41% of low income students manage to graduate within five years) and the increasingly middle-