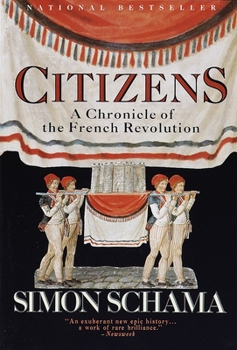

Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In this New York Times bestseller, award-winning author Simon Schama presents an ebullient country, vital and inventive, infatuated with novelty and technology--a strikingly fresh view of Louis XVI's France. One of the great landmarks of modern history publishing, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution is the most authoritative social, cultural, and narrative history of the French Revolution ever produced.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0679726101

ISBN13:9780679726104

Release Date:March 1990

Publisher:Vintage

Length:976 Pages

Weight:2.70 lbs.

Dimensions:1.7" x 6.1" x 9.1"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

A Tremendous Performance

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Citizens is a truly wonderful example of narrative historical writing - a "tremendous performance", to borrow a favourite expression of Simon Schama. The author prefers a more old-fashioned interpretation of the French revolution, which presents the revolution as a drama and focuses on the characters that determine the unravelling of the plot. This choice provides the book with the memorable stories, such as the royal family's comically feckless flight from Paris in 1791, that make it such a delightful read. It is a liberating experience to find a general historical survey that does away with the conventional, stultifying analytical distinctions between economic, social and political factors. Instead, the reader can interact directly - as well as chronologically, which makes it easy to dip in and out of - with the actors and the events without having to navigate around tedious discussions of causal significance or complex arguments with other historians. But it is the skill with which Schama recounts events like the fall of the Bastille that makes this book unique and easily the most enjoyable modern history of the revolution in English. The embellishing vocabulary (readers are advised to have a dictionary to hand), the recurring motifs (the revolutionary obsession with heads, whether on pikes or as busts) and the vivid build-up of tension are the true strengths of this so-called chronicle. It is perfect for the novice reader and the enlightened amateur alike. Citizens demands re-reading for the richness of its description to be fully appreciated, especially its masterful reconstruction of the fascinating and sometimes disturbing culture of the old regime, which is probably the most accessible that exists. The only disappointment is that it ends with Thermidor, in 1794. After 800 pages, one is still hoping for more, which is the highest recommendation possible for this genre of historical writing.

A remarkable, life-changing read

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

This monumental book attempts to chronicle the French Revolution from its inception to the end of the Reign of Terror in 1794, using a slightly different style than most conventional histories. In the preface, Schama notes that studies of personalities have largely been replaced by studies of grain supplies, indicating a pattern to seek explanations for historical events and trends in obscure economic factors, rather than in the personalities of the leading figures involved. This Schama is determined to fight against, and he resurrects the nineteenth-century chronicle, with its emphasis on people, high and low. The first section is largely concerned with the Old Régime, which the author reveals a dynamic and rapidly changing society, where the pace of change was indeed too fast instead of too slow, as the popular perception goes. He meticulously shows the rise of revolutionary and nationalist culture, as well as of a new economic order, and the incapacity of Louis XVI and his governments to deal with the new realities. The accounts of the demise of the Old Regime and the beginnings of Revolution are extremely detailed, but also move at a fast pace, with numerous stories of the participants interspersed in the narrative. Schama's use of primary sources is exhaustive, and sometimes even tends to be overwhelming, but the overall effect is an impressive display of historical writing at its finest. But it is in relating the power struggles within the National Assembly and the Convention that Schama truly shines. We hear the strident rhetoric of the Brissotins and later the Jacobins, calling for the bloody consummation of the Revolution. We are at the side of the major players as they are elbowed aside, which often means assassination or execution. We are taken to the provinces, where the Vendéan revolt and the subsequent massacres of thousands by the revolutionary authorities provide horrifying preludes of twentieth century violence and genocide. Indeed the most striking aspect of the book is just how much the forces of totalitarianism in our time owe to their Jacobin predecessors. The speeches of Saint-Just and Marat could have just as easily been uttered by Lenin. The vast outdoor pageants and revolutionary festivals conceived by Jacques-Louis David could measure up considerably well to Albert Speer's monstrous but impeccably designed rallies for Hitler. Schama pulls off an astounding effect, for as the reader progresses in the story, the revolutionary fervor almost creeps out of the page, and one feels the all-encompassing madness. The ending of the book is bleak, showing a disturbing lithograph of Robespierre decapitating the last executioner amidst a forest of guillotines and in the shadow of a giant chimney of cremation bearing the inscription "Here lies all of France." The Terroristes' own pathetic endings provide no closure, merely a bitter aftertaste of disgust. Schama's contentions are well-reasoned and he succeeds magnificently in exposin

Excellent but revisionist narrative of the French Revolution

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

The French Revolution is one of the decisive landmarks in human history. Though feudalism was long past much of it's vestiges (social, political and economic) remained in some form or other in Western Europe. By the end of Napolean's reign it had all been swept away. Even Metternich couldn't put Europe back together again. For better or for worst the French Revolution set the tone for much of what would follow in Europe. At its worst the Terror was a glimpse into the horrors of the Nazi's and Stalin's great purges. At its best the ideals of the revolution set the tone for free elections, representative government and constitutional law. For revisionist historians it's the former that is the great legacy while for those of the old school it is the latter that is the primary message. Schama's "Citizens" is above all a great narrative history well documented and thought out. Like most who lean toward the revisionist side he is somewhat sympathetic to the regime and the nobility. That information should certainly aid the reader while navigating this well written work. You can't help but admire the combination of writing and research that marks this great book. One note, Schama's area of expertise was not originally the French Revolution but rather the Dutch trading empire and it's aftermath. The strengths of Citizens is non stop chronicle of the actions and interactions of the key members of the revolution's story, from Louis the XVI's incompetence to Robspierre's chilling demeaner. This is an almost epic narrative of the age. It unfortunately, but because of its size, understandably ends far too soon for a complete grasp of the whole era and its aftermath. Definately recommended for students and casual readers of history.

Tour de force

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

This book, in compelling narrative, makes is clear that the French Revolution actually began not with the clamor of the common people but with the blue-blooded aristocracy and the high clergy of the ancien régime who had been enamored with the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the views of the enlightenment (i.e., convincingly demonstrated in the Assembly of Notables convened in February 1787). Moreover, the revolution spilling into the streets of France began not in Paris but in the streets of Grenoble, the actual cradle of the revolution, with the Day of Tiles (June 10, 1788), and from there eventually spreading to the countryside with the grain riots and finally in March through April of 1789 in the concerted defiance of the hated game laws protecting birds and animals. The mobs learned to command the streets after the Réveillon Riots (April 1789) so that by July 14, 1789, they had had ample practice for the storming of the Bastille. One gets to know with almost casual familiarity the important personages in the ancien régime, including those working behind the scene. (This has been heretofore usually the case only with the most bloodthirsty revolutionaries like Marat and Robespierre.) Regardless of what you have been led to believe, the earliest revolutionaries were not bourgeoisie, but nobility and high clergy, many of them functionaries in the old regime. Intoxicated by idealism and Rousseau's sublime concepts of virtue, reason, equality, etc., they had set out to correct real or perceived iniquities in France. Louis XVI's ministers saw the dangers lurking ahead, but seemed impotent to effectively protect the monarchy and solve the problems afflicting France, particularly the looming, serious financial problems and the threat of national bankruptcy. Nevertheless, these old regime functionaries, for the first time, are seen by the author as people of flesh and blood, although with all the frailties of ordinary men when all too often in times of crises - unlike other books in which they are portrayed almost anonymously as faceless aristocrats imbued not in human virtue, but only suffused of arrogance and other vices of idle and luxuriant living.This book argues persuasively that the old regime was of itself undergoing changes of modernity in trade, technology, and laissez faire capitalism influenced by the teachings of the physiocrats, and these changes, rather than being openly welcomed by the people because of the advent of greater economic freedom, were actually decried and resented because these changes brought them insecurity and incertitude. The common people wanted cheap bread and regimentation whereas the lesser nobility wanted to hold onto the only thing left to them - their titles of nobility and what remained of their ancient land privileges, poor as most of them had become. It wasn't the lesser nobility or the bourgeoisie who led in the revolution.From the outset of the revolution, for the most part, the liberal elite coming