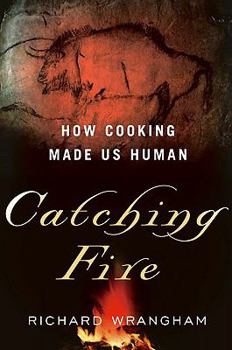

Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The groundbreaking theory of how fire and food drove the evolution of modern humans Ever since Darwin and The Descent of Man , the evolution and world-wide dispersal of humans has been attributed to... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0465013627

ISBN13:9780465013623

Release Date:May 2009

Publisher:Basic Books (AZ)

Length:309 Pages

Weight:0.99 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 5.7" x 8.3"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Me Tarzan, You Make Dinner

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

This is a mind-bending book. While I was reading it, I bored everyone in my family (especially at every meal) with the details of Richard Wrangham's startling thesis: that of all the changes that distinguish ape from man, the ability to control fire and cook one's food comes first. It's cooking, argues Wrangham, that liberates us to travel widely and hunt effectively (other primates spend too much time chewing); it's cooking that creates the conditions for differentiated sex roles (and the relegation of women to the kitchen); it's cooking that denudes us of our hair (the fire keeps us warm), making us better runners (less overheating) and again adding to our ability to travel distances; cooking gives us small guts (well, not mine) and big brains (guilty as charged!). The implications of this thesis are both historical and contemporary. The reader gains insight into how family structure evolved, and at the same time is enlightened about what kinds of foods are really contributing to 21st-century obesity and its related health problems. The epilogue, which explains and criticizes how calories are counted by the food industry, is quite illuminating on this last point. The book is billed as being path-breaking and original. While written for the educated rather than academic reader, it does contain thorough and informative endnotes (they are unobtrusive as you read, since subscripts are not inserted in the text). I have not reviewed these notes completely, but my impression is that many parts of the book, rather than being paradigm changing, chiefly synthesize work on food that has already been done. I do not say this as a criticism -- his references demonstrate his impressive command of the field and range from well known sources (like Stephen Jay Gould) to the most up-to-date breaking scientific studies (for example, evidence that the digestion of hard foods is more costly than soft comes from a scholarly article that at the time of this writing [2009] is in press rather than in print; see p. 255). But it may be that the book as a whole can be characterized mostly as putting together work that others have done. Still, I do think that there are some very original insights here and that the synthesis itself is distinctive. Wrangham is a biological anthropologist, whose academic work is in the study of chimpanzees. The observations he offers about the differences between the organization of human society and that of other primates seem less derivative and related more closely to his his own empirical observations. I would put in this category the insight that it is food rather than sex that really drives behavior. I was fascinated by the speculations on sex roles in which Wrangham engages, which fly in the face of some traditional explanations of the origin of human society in the regulation of sex relationships. He is quite persuasive that the hunter's need for a cooked meal and the gatherer's need for a protected hearth are more fundamental than

What a great idea!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Wrangham marshalls a great deal of evidence from a wide array of fields to claim that the critical development that separated genus Homo -- our extinct relatives and us -- from our Australopithecine ancestors was the invention of cooking. If so, cooking started long before most scholars have previously estimated. Wrangham is a specialist in non-human primates, so his argument is strongest when he is contrasting their anatomy and behavior to humans'. I am no anthropologist, but unitl I hear the other side, I find this pretty persuasive. The book's also a good read.

Important contribution to anthropology

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Anthropology is supposed to be the scientific study of humankind. Unfortunately, since its inception, it has been inundated by carefully disguised pseudoscience - attempts to use scientific data to support the preconceived biases of the investigators. Typically these biases (aka hypotheses) have been ethnocentric and agrocentric, and the arguments used to support them are often composed of flawed logic in the service of false implications. How relieving to read Wrangham's book, which actually appears to draw hypotheses from observations rather than a self-aggrandizing belief system. The author then analyzes realistic and sensible implications of these hypotheses, testing them in a simple but logical way that makes his conclusions seem obvious. This is the kind of book that makes one wonder, "Why hasn't this been argued before?" While his book is rather small and the ideas are not deeply explored, this is largely because the hypotheses that Wrangham presents are quite new. I believe that his ideas will be supported, refined, and expanded by further investigation. While some of his ideas appear outdated or unsupported (for example, he seems to suggest that hunter-gatherers were poorly nourished compared to later farmers, when in fact a substantial body of archeological evidence points to the contrary being true), and he makes some assumptions that are unfounded (for example, that human diets without cooking would be comparable to those of chimpanzees. This is highly unlikely, since pre-humans were bipedal, which suggests a far greater mobility geared toward different food preferences than apes that move on all fours or in trees. It is possible, if not likely, that human ancestors used their greater mobility to extract higher quality food from a larger home range more selectively than chimps.) However, despite these shortfalls, the ideas presented in the book are extremely important to the study of human evolution and anthropology, as well as the endless and robust contemporary debates about nutrition and health. The book reflects something that I have been telling participants in my wild food foraging workshops for years: that cooking and processing food is the most significant human invention of all time. We would be wise to remain aware of that, and I am grateful that this author has increased my understanding of this issue. Indeed, I feel that this is the single most important contribution to anthropology in decades. It is also well written, enough so to keep the interest of the casual reader.

A brilliant and important hypothesis

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Around 1.8 to 1.9 million years ago, Homo habilis (a chimpanzee-like primate, but with a bigger brain and tool-making skills) evolved into Homo erectus. The changes were spectacular: Homo erectus had a 40% larger brain than Homo habilis; looked much more like a modern human than a chimpanzee; had lost its tree-climbing skills, but gained running skills; had a much smaller, and less energy-consuming digestive system (smaller mouth, teeth, jaws, jaw muscles, stomach, and colon); lost most of its coat of fur; and developed a social system based on economic cooperation: the husband hunted, the wife gathered and cooked, and they shared the food. Wrangham argues that Homo habilis learned to control fire and that that fact is both a necessary and sufficient explanation for this evolutionary leap. First, fire is used for cooking, as all primates find cooked food more delicious (even monkeys know to follow a forest fire to enjoy the cooked nuts). Cooking gelatinizes starch, denatures protein, and softens all foods, permitting more complete digestion and energy extraction. As a result, the food processing apparatus shrinks, freeing energy to support a larger brain. (After the gut shrinks, the animal can no longer process enough raw food to survive, but is dependent on cooking. Wrangham reports that humans with even a large supply of well-processed, high-quality food lose both weight and reproductive capacity on a raw diet, and that there are no known cases of a modern human surviving on raw food for more than a month.) Second, fire provides defense against large carnivores, permitting Homo erectus to descend from the trees and live on the formerly preditor-dangerous ground. The group would sleep around the campfire while an alert sentinel watched for predators, which would be repelled with a fiery log. Living on the ground led to the development of long legs and flat feet--ideal for running. Third, fire permits loss of fur, as a hairless animal could warm itself by the fire. Hairless animals can dissipate heat much more quickly, giving them the ability to outrun furry animals. Homo erectus could simply chase a prey animal until it collapsed from heat exhaustion. Fourth, cooking permits specialization of labor. Without cooking, both males and females must spend most of their day gathering and chewing vegetable matter. Because hunting success is unpredictable, they could devote relatively little time to it, because an unsuccessful hunter would have inadequate time to gather and chew vegetables. Cooking, however, reduces chewing time from 5 hours per day to 1 hour, freeing time to hunt. A hunter who returned empty-handed could still enjoy a cooked vegetable meal and have time to eat it. Here Wrangham (who teaches, inter alia, a course named "Theories of Sexual Coercion") indulges in academic feminism when he says that "cooking freed women's time and fed their children, but also trapped women into a newly subservient role enforced by male-dominated cul

A New Theory On What Makes Us Human

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Anthropologists, historians, and theologians have many theories about how humans became "human". Dr. Richard Wrangham here posits that humans became "human" because we learned to cook our food over a million years ago, when homo erectus first tamed fire. Conventional theory holds that humans began to cook their food long after their path diverged from other primates, so its interesting to read Dr. Wrangham's belief that cooking was a cause rather than an effect. Dr. Wrangham provides some fascinating material on how humanity began to physically separate from the apes, and how eating cooked food intensified the process and hurried it along. This has the potential to become impenetrably technical, but Dr. Wrangham writes clearly with the general reader in mind. I also enjoyed his coverage of the claims of present day raw-foodists, some of whom he interviewed. After that chapter I was left feeling simulataneous admiration for the dedication of raw-foodists and repulsion at the thought of following a similar diet myself! Dr. Wrangham has a good ear for an entertaining anecdote, such as the story of poor Alexis St. Martin, who survived a horrifying injury that permanently opened his stomach, thus involuntarily becoming an assistant to a researcher who wished to observe the process of digestion. The text of this book is only about 200 pages. It is exhaustively researched and documented, with over 40 pages of notes, a 30 page bibliography, and a 20 page index. It will appeal to students of early man and to followers of Michael Pollan, with whom Dr. Wrangham shares a concern that humanity return to more natural and less highly processed food.