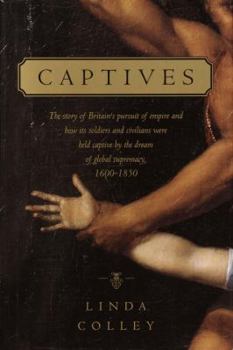

Captives: The Story of Britain's Pursuit of Empire and How Its Soldiers and Civilians Were Held Captive by the Dream of Global S

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In this path-breaking book Linda Colley reappraises the rise of the biggest empire in global history. Excavating the lives of some of the multitudes of Britons held captive in the lands their own... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0375421521

ISBN13:9780375421525

Release Date:January 2003

Publisher:Pantheon Books

Length:438 Pages

Weight:1.75 lbs.

Dimensions:1.4" x 9.8" x 8.6"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

a new perspective

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

I very much enjoyed the book. It was, to me, a new perspective on England, the Empire and British influence in very different parts of the world. I was especially interested in the North American section, but since I enjoyed her writing style so much I forged ahead into the Asian section. I found the book to be densely packed with ideas new to me and topics that generated my interest in learning more. I recommend this book to those interested in American Revolutionary history as well as British history in general.

"Airbrushed from history . . . "

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Once, i hoped for a truly comprehensive survey of the British Empire and its global impact. This excellent book is almost the response i wished for. Colley examines "a quarter of a millennium" in an overview of three stages of Britain's expansionist adventure. From the start, she reminds us, Britain's miniscule population and limited resources made it an unlikely candidate for global expansion. Contending with nations better prepared or more experienced in empire-building, the founding of the British Empire was typified by false starts and unlikely events. In using the accounts of prisoners - kidnappees, prisoners of war or other captives, Colley is able to point out how both public views and policies changed during the growth of the Empire. Most important, she argues, is the need to dispel notions that the empire was monolithic in concept or development. Clearly organised and written with clarity and intensity, Colley opens her study with an example of glaring failure. How many remember Britain's occupation of Tangier on the west coast of Africa? The city was part of a queen's dowry in 1661, giving Britain a control point over the Mediterranean trade routes [Gibraltar came under British power in 1701]. With Spain, France and Italy, not to mention the Dutch, all expanding their sea-going commerce, Tangier was a key location. The British poured immense sums into Tangier to create a fortified city, but it was lost less than a generation later. Colley explains how relations with the "Barbary" states of North Africa drove British foreign policy for many years. Those relations included ongoing efforts to redeem captives taken by corsairs, swift vessels that even raided coastal areas of the British Isles. Britain's next expansionist efforts were even less calculated - the settlement of North America. While religious and other dissident groups founded communities along the eastern shores of North America, Britain's policy toward them remained ambivalent. Unlike the mostly military Mediterranean and Indian ventures, Colley says, North America focussed on settlements. When captives were taken, they might thus be whole families, with a wide age range and including more women that would be the case elsewhere. Accounts of captivity, therefore, were different from Tangier. Men taken by the Barbary corsairs might adopt local dress, customs, language, even Islam. This blurred the image of Muslims as the Other - an identifiable enemy figure. In North America, as colonies expanded, the Native Americans became more demonised in tales of warfare and capture. Even so, she notes, the North American enterprise was "poly-ethnic", with many nationalities arriving and the use of favoured Native American tribes as allies. Britain's Indian incursions, Colley points out, added new dimensions to imperial imagery. Severe defeats and sepoy [Indians acting for British rulers] uprisings forced reflection on colonial costs and eroded prestige. Captivity

The Cost of Empire

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Colley makes it easy to understand why English is the world standard language today: a small population could only control as much as it did by co-opting vast numbers of people and this meant expending captives at a fairly high rate.Their story is the story of the Empire at its bleeding edge.Using captives to illuminate imperial expansion is a novel idea and well done.

If you know nothing about the British Empire...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

...this would be a good book. But if you know more this book will be slightly disappointing. Welcome to Linda Colley's new book about the British Empire which looks at it through the unusual prism of captive narratives. Colley's new book is oddly similar to her last book, "Britons", having approximately the same number of pages (c.380), the same number of illustrations (c.75-80), and the same number of notes. Colley's book is part of a particular British history genre. Following in the path of Simon Schama's "Citizens," these books are often lavishly illustrated and rely less on systematic research than amusing and telling anecdotes. Although the authors often have strong opinions, their interest lies less in their originality than at their ability to bring to the public an element of scholarly research that hitherto been overlooked. Similar authors include Orlando Figes, Niall Ferguson, and, in a pinch, Andrew Roberts.Colley's book can be divided into three parts. First, she discusses the narratives of Britons captured by the Barbary and Algiers Corsairs in the 17th and 18th centuries. Second, she uses the narratives of those captured by Native Americans to highlight the relationship between the Britons and their American colonies. Thirdly, she looks at those Britons captive in India, either at the hand of rival kingdoms, or as soldiers captive in their own army. Throughout this book, Colley has a sharp turn of phrase ("The thin red [Imperial army] line was more accurately anorexic.) And she has an eye for fascinating detail. We learn that in the 1820s, two out of every five soldiers in Bermuda were whipped, and we are told about a particularly horrifying one in which the victim was whipped to death such that his back was "as black as a new hat." We learn that Irish soldiers in the 1680s in Algiers spoke in Gaelic to each other so that the English Protestants helping the besieging Moroccans wouldn't understand. We learn that not only did the British have campaigns for the benefit of the French prisoners they caught during the Seven years War, but the French held similar campaigns for the British prisoners they caught. We also get a sense of the continual expansion of the Empire. In the relatively quiet decade of the 1840s alone, Great Britain gobbled up New Zealand, Natal, the Punjab, and Hong Kong among other places. Colley has two messages from her captivity narratives. First, there is the constant ambiguity of response. The British often could not help admitting the civilization of the Ottomans, the courage of the native Americans, and the resourcefulness of their Indian rivals. Many Britons admitted even more, and many crossed over to the other side, although the attempt to do so had their own difficulties and ambiguities. Colley constantly, indeed somewhat repetitively, argues that there was no monolithic racism. Secondly, she points out the constant vulnerabilities of the empire. Imperial overstretch was always a prob

Colley Borders On Captivating

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

I love books that get you to reexamine your attitudes or to at least look at something familiar in a new way- and not just for the sake of "novelty", but because the author has something important to say. "Captives" is such a book. What more can be said about the British Empire? The answer turns out to be quite a bit. Ms. Colley takes a look at four areas: North Africa, North America, India and Afghanistan- and examines the "captivity experiences" of white Britishers...soldiers, East India Company representatives and their families, merchant seamen, etc. This alone would be fascinating, because it is a subject rarely dealt with. But in addition to the "human interest/storytelling" aspects of the book, Ms. Colley has some serious, scholarly points to make. One is that, for the period covered in this book, it was certainly never clear, not even to the British, that there was going to be a British Empire. Britain was geographically small, had a small population and therefore a small army, and technology wasn't yet so far advanced that the British could feel confident that their weapons were automatically going to win battles or intimidate people. Another point the author makes is that due to consistent manpower shortages, the British could never just rely on their own forces. They had to depend on local, native troops. This was most obviously true in India, but it was also true in North America. The British had no choice other than to use Native American warriors against the French during the Seven Year's War and Native Americans and Blacks against the "rebels" during the Revolutionary War. Since the British needed these "outside" forces it influenced the way these "outsiders" were perceived and treated. For example, while Americans of European ancestry would caricaturize Native Americans as "savages", the British, in paintings of the period, would tend to show Native Americans in a way which, they felt, made them look "civilized" i.e.-in European dress or they would give them somewhat European features or mannerisms. Politically speaking, the British had to be careful not to antagonize or alienate these "mercenary" forces. They needed them too much. So, for example,if Native American forces killed prisoners who had surrendered or scalped civilians, the British sometimes just had to look the other way. In India, the absolute necessity to rely on native Indian troops influenced the way the British saw these troops. Ms. Colley cites quotations showing the sepoys were seen to be abstemious, intelligent and reliable, while the common soldier from Britain was seen to be a drunken, thieving brute who had to be kept in line with the lash. This punishment was much more likely to be used on the soldier from Britain, by the way. If the sepoys mutineed or deserted, that would result in the loss of about 85% of the British forces. As far as North Africa went, since they needed to hold onto Gibraltar and Minorca, the British had to "cut a deal" with the Barbary