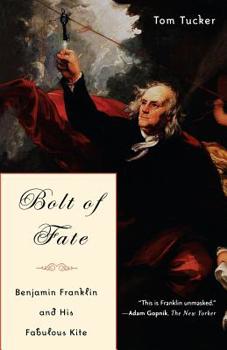

Bolt of Fate: Benjamin Franklin and His Electric Kite Hoax

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Every schoolchild in America knows that Benjamin Franklin flew a kite during a thunderstorm in the summer of 1752. Electricity from the clouds above traveled down the kite's twine and threw a spark from a key that Franklin had attached to the string. He thereby proved that lightning and electricity were one. What many of us do not realize is that Franklin used this breakthrough in his day's intensely competitive field of electrical science to embarrass his French and English rivals. His kite experiment was an international event and the Franklin that it presented to the world -- a homespun, rural philosopher-scientist performing an immensely important and dangerous experiment with a child's toy -- became the Franklin of myth. In fact, this sly presentation on Franklin's part so charmed the French that he became an irresistible celebrity when he traveled there during the American Revolution. The crowds and the journalists, and the ladies, cajoled the French powers into joining us in our fight against the British. What no one has successfully proven until now -- and what few have suggested -- is that Franklin never flew the kite at all. Benjamin Franklin was an enthusiastic hoaxer. And with the electric kite, he performed his greatest hoax. As Tucker shows, it was this trick that may have won the American Revolution.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1586482947

ISBN13:9781586482947

Release Date:March 2005

Publisher:PublicAffairs

Length:297 Pages

Weight:0.73 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.3" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

2 ratings

Absorbing character study

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

[This review was presented at a meeting of the American Revolution Round Table in New York City, October 2, 2007.] The title ... might lead you to think we're pondering an academic version of Discovery Channel's Mythbusters, but happily this book is a great deal more, a serious contribution to the history of science and its interplay with society. One might think, since people have undoubtedly always received shocks when shuffling across carpets, that natural philosophers would have sustained a steady curiosity in the phenomenon through the centuries, and made consistent but plodding progress in examining it. Well, apparently not. Beginning around 1743, and peaking over the next ten years, electricity was suddenly a huge European fad that gripped everyone, from serious scientists to high society to middle-class dilettantes to fair-going country bumpkins. It was suddenly realized that static electricity could be generated at will, by creating friction against a spinning glass jar; and with it, you could not only attract confetti up to your hand, you could make bells ring without touching them, or inflame a glass of brandy. Better yet, you could--in the pure interest of science--ask a willing, electrically-charged young man and a willing but neutral young lady, to touch, and enjoy the mildly prurient result of their shared convulsive shock. In 1746, the invention of the Leyden jar, forerunner of the electrical storage battery, made these parlor tricks into a new mass entertainment, fascinating everyone from village taverns to royal palaces. One who caught the bug was the successful Philadelphia entrepreneur, Benjamin Franklin. In March 1747, Franklin wrote a friend that he was "totally engrossed" in the subject. Tucker, who has written on the history of invention before, goes to some pains to demonstrate that Franklin made genuine scientific contributions to the subject over the next few years. Among other things, in the process of meticulous experimentation on the properties of electricity, it was Franklin who coined positive, negative, plus, minus, and battery as electrical terminology. Franklin kept current with scientific progress in Europe, and he knew that he'd done original and valuable work. He reported his efforts in the detailed epistolary style of the day to members of the British Royal Society. But not only did the colonial unknown get no thanks and no recognition for his labors, one of the best-known British scientists, the man to whom his letters were entrusted, William Watson, proceeded to plagiarize him. This is the point at which Tucker's revisionist thesis kicks in. A subsequent missive Franklin wrote in 1750 contained what was known as the "sentry box experiment," in which a long iron rod was to be erected vertically into the sky and bent around into an open-fronted sentry box so that the bottom of the rod, hanging free, would not get wet, and then a person could supposedly conduct electrical experiments with

Fun Book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

I enjoyed this book because the author obviously likes and respects Benjamin Franklin so the story of how he flew the kite is one of a celebration of Franklin. As an ex-US History I know the playful mischiefness wit of Franklin is lost in our classrooms. The book does a great job of exposing this other side of Franklin so often lost.