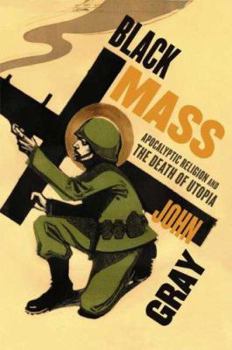

Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

For the decade that followed the end of the cold war, the world was lulled into a sense that a consumerist, globalized, peaceful future beckoned. The beginning of the twenty-first century has rudely disposed of such ideas--most obviously through 9/11and its aftermath. But just as damaging has been the rise in the West of a belief that a single model of political behavior will become a worldwide norm and that, if necessary, it will be enforced at gunpoint...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0374105987

ISBN13:9780374105983

Release Date:October 2007

Publisher:Farrar Straus Giroux

Length:242 Pages

Weight:1.10 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 6.3" x 9.4"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

Difficult to know where to begin...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

First I want to get something off my chest: who, over at the publishing company, came up with the godawful cover for this edition of the book? It looks like something out of a 1940's sci-fi comic book, or taken from one of those Bobby Sands graffiti pictorials you might see on an old Belfast brick wall - totally lame. And it's a shame, too, because there is nothing lame about Gray's dour, penetrating, sobering book. It is an unsparing critique of not only utopianism, but the very idea of progress (in human terms) itself. Gray in effect argues that the Enlightenment project, in a profound sense, is a sort of fraud, in that it has largely occupied the "framework of thought" created by Christian theology, while claiming to have escaped that framework altogether by the relatively trivial act of substituting other ideals for a god figure. Characteristics of that framework include ideas of a linear march of human history towards some end or final culmination (apocalypse), the possibility of moral or ethical progress, and belief based not on any sort of evidence or precedent, but on nothing more than blind faith. Gray along the way devotes quite a bit of time to the Iraq War...but it's hard to do a book this dense any real justice in a review. Suffice to say, I find many of his arguments distressingly compelling (perhaps partly because of his terse, clear prose). The only concern I have with this book, and with all other books like it, is that it attempts to establish what I might call genealogies of ideas - one (or more) ideas begat other ideas, and those ideas in turn begat these ideas, and these ideas begat those others, and "this is how X people got to Point Y, and how Point Y came to influence the world", with the whole description being suffused with the implication that *logic* was something of the main spur of generation (Idea A logically follows from Idea B)...as though a genealogy of ideas was conceivably as tidy and clear-cut as a biological reproductive chain. But I always get the sense that such genealogies themselves are more the products of our own need to believe that there was some kind of *rational order*, or even just any intelligible process... So, for example, was Hitler a child of the Enlightenment? Well, notes Gray, he was inspired by science - Darwinism in particular - and his racism and race policies were amply justified by leading scientific authorities of his day (all over the West). But could it not be as easily argued that he was a child of outrageous romanticism, of Nietzchean Dionysianism, where *to feel* and *to act* and to *impose will* is far more important than to think or contemplate or argue or justify? Gray argues that Marxism too was but another Enlightenment fruit; but again...when the egalitarianism impulse is so deeply rooted in our psyches, so far beneath any reach of mere rationality, so at its root *religious*, how can we say that it was more the product of reason, than unreason? Maybe another way of

Enlightening

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Like all books by John Gray, Black Mass is a compelling example of the power of an overwhelming and logical examination of vital events. At this point, I would classify Mr. Gray as one of the five top philosophers in the English language. In addition to the impeccable quality of his reasoning, he writes in an accessible and beautiful Englsih, without all the word-splitting typical of philosophers, particularly of the French breed. Kudos!

Un-realising a "perfect" world

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

It's not easy categorising John Gray. He's generally listed as a "philosopher", but he rarely delves into the roots of human behaviour. His philosophy is founded on recorded history. Like most modern "philosophers", his arena is the canon of Western European tradition and practice. That approach, at least in Gray's hands, makes him more political commentator than philosopher. The shift of emphasis doesn't erode his thinking prowess nor his ability in expressing what he has derived from it. His prose is clean and unpretentious, almost hiding the power of the thinking behind it. In this exciting little work, Gray examines the history of modern "utopian" ideas - their misconceptions and their persistence. The idea of utopias has long diverted us from confronting realities, Gray suggests. This self-generated departure tends to hide consequences of our acts until it's too late to deal with them successfully. Naturally, one of his glaring examples of this situation is the Anglo-American invasion of Iraq. Gray demonstrates how it was planned intentionally long before the causes were manufactured for it. The planning was clearly utopian in that the intentions were delusionary and inappropriate. Both governments declared their intention - based on false pretenses - to "extend democracy into the Middle East". This ambition was expressed without any perception of whether it would be welcomed. It's an underlying principle of utopian thinking, Gray observes, that a society can be re-created from within or imposed from the outside. The failure of such thinking is readily apparent in Iraq - a war that has lasted longer for the US than WWII. Utopian ideas have been seeded on infertile soil. In explaining how the utopian idea arrived in the Middle East by way of the US-UK "special relationship", Gray skips lightly over Thomas More's original idea to the Enlightenment era. There is a link, however, in that while we are generally taught that the Enlightenment thinkers were building a secular world, they were relying on Christian precepts to expound their ideas. "Improvement" was the means of overcoming disparities in the human condition, and the State could replace the Church in making beneficial change. Among other virtues of this thinking was that it seemed realisable within human timespans. In the 20th Century, a wide variety of such proposals were tried, and Gray brings Marxism, the hippie communes of the 1960s and the Fascist-Nazi movements into the same paddock. Once thought as a "Leftist" ideal, Gray is unsurprised that it is now the policy of choice of the "neo-cons" and their supporters on the "Christian Right". Yet, it seems that no matter where on the political spectrum utopians arise, they continue to commit similar blunders. The goal blinds them to the perils of trying to achieve it and utopia becomes tragedy. It's easy to peg Gray as grim or dismal. That's a common label pinned on those who seek to have us confront realit

Save us from salvation

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Picking up where he left off in his genuinely iconoclastic book "Straw Dogs," John Gray turns his attention to the ineluctably human penchant for utopia and apocalyptic fantasy. His style here is less abrasive but no less bracing. A British commentator recently wrote of Gray, "He is so out of the box it is easy to forget there was ever any box" - which fairly describes the intellectual jolt he'll deliver to readers dulled by boxy thinking. The previous reviewer has done a decent job of describing the argument, but any summary misses the electricity that hums in Gray's sentences. Gray's unsparing synopsis of the neo-conservative fantasy that led to the debacle in Iraq will have patriotic Americans grinding their teeth in fury at the waste of American and Iraqi lives and the betrayal of American ideals. He also lambasts liberals who delude themselves about "inalienable" human rights, and minces no words about born-again Christians who've sanctioned and supported the torture and carnage, which leads him to a grim conclusion: "Liberals have come to believe that human freedom can be secured by constitutional guarantees. They have failed to grasp the Hobbesian truth ... that constitutions change with regimes. A regime shift has occurred in the US, which now stands somewhere between the law-governed state it was during most of its history and a species of illiberal democracy. The US has undergone this change not as a result of its corrosion by relativism ... but through the capture of government by fundamentalism. If the American regime as it has been known in the past ceases to exist, it will be a result of the power of faith." (pp. 168-169) Gray is explicit about the folly of religious myths, but he accepts that "the mass of humankind will never be able to do without them," just as he dismisses "militant atheism" as a "by-product of Christianity," mocking its pretensions at evading the conundrums of theology. He's equally clear on the ineradicable future of terrorism. "Nothing is more human than the readiness to kill and die in order to secure a meaning in life." (p. 186) Following the bleak logic of these observations to their conclusion, he can only advocate a clear-eyed realism about the nature of human being - which he confesses may in turn be a self-deceiving hope: "a shift to realism may be a utopian ideal." As I read "Black Mass," I couldn't help recalling the work of William Pfaff, who as a political analyst practices the realism Gray recommends, and whose fine study "The Bullet's Song" examines the "redemptive utopian violence" as it was envisioned by a rogue's gallery of 20th century artist-intellectuals. Neither of these books are comfortable reading; neither offer a panacea - because (as Gray puts it) "there are moral dilemmas, some of which occur fairly regularly, for which there is no solution." It's December, the time of year when voracious readers start compiling their "best of" lists. "Black Mass" (despite its silly title) ranks a