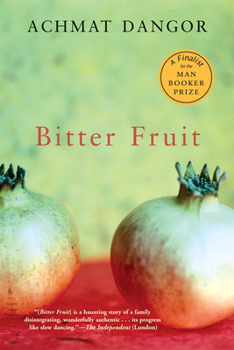

Bitter Fruit

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

With the publication of Kafka's Curse, Achmat Dangor established himself as an utterly singular voice in South African fiction. His new novel, a finalist for the Man Booker Prize and the IMPAC-Dublin Literary Award, is a clear-eyed, witty, yet deeply serious look at South Africa's political history and its damaging legacy in the lives of those who live there. The last time Silas Ali encountered Lieutenant Du Boise, Silas was locked in the back of...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0802170064

ISBN13:9780802170064

Release Date:March 2005

Publisher:Grove Press, Black Cat

Length:288 Pages

Weight:0.80 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.5" x 8.4"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Thought Provoking

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

This is one of the best books I have read in my life! I never heard of this author, I just happened to pick up the book while I was in an airport. I was so engaged with this book I could barely put it down! As an African American who has never been to South Africa I felt this book was absolutely extraordinary and I loved the intertwining of so many characters while not losing the identity of any of them. I recommend this book to anyone who is interested in books that are for pleasure but also cause you to reflect.

Searing Account of Racially Driven Confects Within a Post-Apartheid Family

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Author Achmat Dangor has given me a penetrating look at post-apartheid South Africa that I could not possibly get from a newscast. His superb novel resonates deeply with the legacy of racism that lingers well after official policies have supposedly liberated all of the country's residents. Dangor is intimate with the subject of apartheid as he worked to defeat it there and then participated in the slow process of rebuilding after the African National Congress came to power. He divides the book into three parts - Memory, Confession and Retribution - which suggests what direction the book will go, but it's a surprising and involving journey every step of the way. The focal point of the novel is Silas Ali, a former political activist who has joined the new government as a lawyer working with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He lives with his wife, Lydia, a nurse, and their grown son, Mikey, in a township near Johannesburg. There is an inherent irony to their existence - Silas works with the government agency that grants amnesty to those who committed crimes under the old regime, but he and his family remain traumatized by the one hate crime that happened to them. It involves a twenty-year old rape and the sudden reappearance of the perpetrator, a white policeman named François du Boise. Much like Andre Dubus circles the dramatic wagons in his short story collection of revenge and retribution, "In the Bedroom", Dangor does a masterful job in building the tension within the family. Silas doesn't confront du Boise, so the much needed cathartic release is instead directed at the family, triggering a chain of events that leads to its disintegration. The sharply observed narrative carefully interweaves the differing perspectives of Silas and Lydia. Whereas Silas is deadened by his own stoic resignation of what occurred so long ago in the past, Lydia's suffering is far more intense as she irrevocably retreats into herself. The irony is that there is no truth and reconciliation at home as Silas continues to fulfill the concept at a national level. The unfinished business between Silas and Lydia is palpable and ultimately shattering in bearing the "bitter fruit" of the title. Caught in the middle literally is their psychologically conflicted son Mikey, who has internalized his parents' pain. As he relives the past through his mother's diary, he finds out revelations which make him feel more emotionally detached than he is but subsequently lead him to take matters into his own hands. Dangor provides such vivid detail in his account that it's hard to put down.

The ever-turning wheel of history

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

As a young man, Silas Ali is a member of Nelson Mandela's African National Congress, but Silas' wife, Lydia, is unaware of the degree of his commitment. Early in their marriage, Lydia is raped by Lieutenant DuBoise, an Afrikaans officer who takes her with impunity before her helpless husband. Such atrocities are commonplace at that time, but the event remains a personal shame until twenty years later, when Silas encounters DuBoise in the street. South Africa is now awaiting the results of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, an attempt to make peace with the brutal excesses of the country's past. The chance meeting with DuBoise stirs up years of anguish and resentment for Silas and Lydia, throwing their troubled marriage into stark relief before their extended family, but especially their son, 19-year old Mikey. Used to his parents' lack of communication and marital idiosyncrasies, Mikey secretly reads his mother's diary, which holds stunning revelations, a shocking truth that will shake the foundations of Mikey's world. Silas has the task of informing Lydia that DuBoise has requested a public apology before the Commission and has named her as one of his victims. Although Lydia begs her husband to stop DuBoise, Silas cannot and their lives are clouded by this knowledge. Lydia watches as her husband becomes even more isolated, her son more distant: "She sees in Mikey an enslavement to another, more puritanical God: his will." For his part, Mikey dismisses the older generation, with their need for "legacy", envisioning themselves as "heroes in the struggle". The nature of betrayal is exposed, leaving Silas, Lydia and Michael without framework as the past turns against the future, the truth destructive, shattering the fragile walls of family. Towards the end of the novel, Michael is told the story of his grandfather, a harrowing tale set in motion when the British occupied India, forcing European values upon their subjects, the seed of resentment planted in the early days of Imperialism. Much of the chaos unleashed has been years in the making. A product of the new South Africa, Michael reaches for the roots of his Muslim past, bringing him face to face with murder, both a personal and generational vengeance. The family, divided by self-interests, is a reflection of the country, factions oblivious to common ground. The novel is perfectly written, emotionally spare, yet with a subtle intensity that unveils the secret shame and hidden truths complicated by corrupt politics and the betrayals of power. Each character startles awake, as if from a long dream, able to survive only in another, freer identity. The true nature of change is abundantly clear and the enormous price it exacts. Dangor's story is personal, a reenactment of a familiar tragedy. Indeed, in his novel "rape is a metaphor for the abuse of ordinary people in South Africa." In a world defined by Apartheid, newly released from its constrictions only to be cast into the nightmare of

searing novel

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

This is a powerful novel set in post-apartheid South Africa. It focuses on the lives and feelings of three people in a family, and the impact of an act of violence during the days of apartheid on their lives in post-apartheid South Africa. It is well written and moving, about people and their personal foibles, their pain and isolation, and also evokes very believably the greater political scene - the political climate in South Africa just as Mandela is about to step down as president. I could not help comparing this book to The Kite Runner and feeling that it was the superior book - better written and tighter, and yet it has been The Kite Runner that became the best seller!

A family and society in bitter transition

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

In Achmat Dangor's masterful "Bitter Fruit", post-apartheid South Africa confronts the brutal scars of its torrid past the way Silas, Lydia and Mikey Ali struggle in vain to shake off the spectre of evil that haunt their present and wreck their chances of staying together as a family. The "bitter fruit" imagery is resonant of the poison that infects their relationship with each other and members of their extended family and friends. Lydia's bitterness at Silas' cowardly complicity turns into anger and despair that only a clean break can dispel. More tragic still for Mikey, himself the "bitter fruit" of his mother's rape by a white security official, who is deprived of any means of confronting the open secret of his own paternity until he finds the perfect outlet for a practice revenge before the inevitable happens. Our sense of Mikey's psychological state crystallizes the moment we discover that he covets signed originals of published classics stolen from his teacher's home. His identity crisis, coupled with his search for his family's roots and his own biological identity parallels that of South Africa's confused present as the country struggles to emerge from the trauma of its apartheid past. Incest, a recurring theme in the novel, is also symbolic on two levels, of the perverted self-hatred that resides and festers from bleeding wounds in the human heart as well as of the social disequilibrium that persists in a nation in transition. Dangor's eloquence is both precise and poetic. His style achieves a nicely judged balance, allowing him the facility to explore the interiors of the human heart without sacrificing the demands of tempo and momentum in a gathering plot. The shattering climax isn't as much shocking as in the way it is so economically and unsensationally told. "Bitter Fruit" is an excellent novel and fully deserving of the lavish critical praise heaped upon it. Highly recommended.