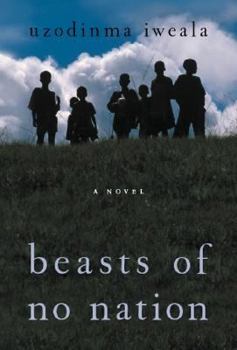

Beasts of No Nation

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The harrowing, utterly original debut novel by Uzodinma Iweala about the life of a child soldier in a war-torn African country--now a critically-acclaimed Netflix original film directed by Cary Fukunaga (True Detective) and starring Idris Elba (Mandela, The Wire). As civil war rages in an unnamed West-African nation, Agu, the school-aged protagonist of this stunning debut novel, is recruited into a unit of guerilla fighters. Haunted by his father's...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:006079867X

ISBN13:9780060798673

Release Date:November 2005

Publisher:Harper

Length:160 Pages

Weight:0.55 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 4.9" x 7.1"

Related Subjects

Betrayal Friendship Hope Loyalty Power Dynamics Trauma Violence Literary Fiction War Fiction ContemporaryCustomer Reviews

5 ratings

a powerful, difficult tale that rings true

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Iweala has a written a short but potent book about a West African boy named Agu (between 9 and 12 years old, according to an interview with the author) who is abducted into a unit of child soldiers. We follow him as he grows up far too fast, experiencing the horrors of guerrilla warfare. This book is not for the faint of heart: we see killing, rape of women by child soldiers, rape of child soldiers by cruel adult commanders. Yet the book feels real: Iweala read several autobiographies of child soldiers as well as reports from organizations like Amnesty International and texts of child psychology. This book is disturbing only because our world is disturbing. The language of the book is challenging, written in a pidgin English adapted from what Iweala has heard on his many visits to Nigeria (he is American, born to Nigerian parents). As a result, it took me a while to work through the slim 150-page volume; but the work is rewarding, and it serves as a metaphor for the work of delving into the foreign world that the novel depicts. As Agu says, much of what he experiences is "making me to feel good and it is not making me to feel good," reflecting the duality of the war experience: the adrenaline reported by those who kill contrasted with the horror at the actions, both experienced simultaneously. This book was listed as one of the New York Times notable books for 2006; and Metacritic, a website that brings together professional reviews from major newspapers and magazines, collected 10 outstanding reviews and 8 positive reviews: none were unfavorable or even mixed. (I've never seen a book with such good reviews.) I read another novel about child soldiers this year: Moses, Citizen, and Me, by Delia Jarrett-Macauley. That book leaves much more to the imagination, which fails when the context is so far from the reader's experience that the reader's imagination paints a vague, sanitized portrait. Iweala spells it out: it's ugly, but it's a piece of our world. It reminds me of an exchange at the end of the film The Mission, in which the Portuguese representative Hontar seeks to justify the church representative Altamirano's actions, saying, "The world is thus," to which Altamirano responds, "No, Señor Hontar. Thus have we made the world." * Note: the background that I mention above comes from two interviews with the author, one by Andrea Sachs, published in TIME on-line on 29 November 2005, and the other by Robert Birnbaum, published in The Morning News on 9 March 2006. The exact language of the quote from The Mission is from the Internet Movie Database.

Essential Reading

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

I found this book absolutely gripping. It's the perfect length for even the most time-pushed, attention deficient of us - this vital tale of becoming set in war-torn West Africa had me so immersed that I devoured it in one reading. Although the overall theme of the book is extremely harrowing, Iweala doesn't overplay the horrific elements in his story. Instead, because the story is told from the perspective of a shell-shocked child in his naïve, unfamiliar, and awkward vernacular, such events are recounted with an emotional detachment similar in effect to the work of Primo Levi. There is more for our imagination to engage with, this serves only to make it more moving. Momentum in the narrative is generated through the growing compassion felt for our young narrator, Agu, as he is wrenched from an idyllic and precocious childhood into complicity with a world of senseless violence and civil war that he is too young to understand. He faces an acute dilemma - to kill or be killed - and is in a permanent state of conflict as the morals he learned from the warm and peaceful community that nurtured him sit at odds with his instinct for survival, which lies in a tragic necessity to please the brutal guerilla group that pillaged his village and probably killed his father. Detached descriptions of savage rape and murder are juxtaposed with touching recollections of his loving upbringing and the culture that he is now, unwillingly, helping to destroy. These pre-war accounts tell of a West African (we are never given a specific country) way of life and heighten a sense of loss and injustice, of innocents getting dragged into a conflict that they never wanted. If you have read books like A Clockwork Orange (also a book about coming of age, but set in a fictional dystopia rather than in an historical anarchy) you will not have difficulty adjusting to the language Iweala deploys - it's all in English, you just have to mind the tenses. You will probably also really enjoy and appreciate the vernacular style that takes you much deeper into the character and the rhythms of the world that he describes. These days it's all too easy to become absorbed with the war our government started in Iraq, and to forget all the other, often more atrocious wars taking place elsewhere. This book raises awareness of just how intolerable life is for so many people in West Africa, and inspires one to read more about this situation. If our governments were as committed as they say they are to creating world peace, they would address issues of poverty and dictatorship in Africa, rather than creating more death and disorder by channeling their resources on the oil-rich Arab states.

A Classic tale of survival and redemption

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

It doesn't matter that the West African nation, which provides the setting for this unsettling story, remains unnamed. It could be any country afflicted by hatred, and buckled by mistrust and murderous civil war. What resonates in this fierce, gripping novel is the harrowing narration of Agu, a child soldier forced into conscription at the point of a gun. In this staggering debut, ''Beasts of No Nation," Uzodinma Iweala, a 23-year-old Harvard graduate, has written a novel about the perversity of war, and the fragility of humanity. It's all the more shattering viewed through the eyes of a schoolboy who is both terrified and seduced by the meaningless slaughter which first claims his father, then his own childhood. Though this is a work of fiction, this novel is based in terrible truths. In countries such as Sri Lanka and Somalia, children are coerced into the kinds of internecine conflicts that can claim hundreds of thousands of lives, even as they smolder unchecked and unreported for years. In his cadenced vernacular, Agu bears witness for those children. Prior to his soldier's life, Agu loved to read, so much so his mother called him ''professor." The son of a schoolteacher father, Agu's favorite book is the Bible, both for its soft, gold-embossed cover, and its magnificent -- and violent -- stories about Cain and Abel, David and Goliath. Such memories of his gentle family life, before his mother and sister were scooped up by UN peacekeepers and his father shot dead by guerrillas, sustain Agu through his brutal days and nights. Under the vicious sway of Commandant, a rebel leader, Agu becomes a killer, but what choice does he have? Only death awaits those who refuse these hard men. Killing, Commandant tells Agu, ''is like falling in love." Yet when Agu thinks of murder, he imagines himself burning in the hell he once read about in church. Still, bullied by Commandant, who literally squeezes the boy's trembling hand around the handle of a machete, Agu hacks a man to death. ''I am hitting his shoulder and then his chest and looking at how Commandant is smiling each time I hit the man," Agu says. ''It is like the world is moving so slowly and I am seeing each drop of blood and each drop of sweat flying here and there." For all the violence, the true war rages within Agu. He wants to be a good soldier and even finds himself sometimes ''liking how the gun is shooting," and enjoying ''how the knife is chopping" when he's killing someone. At the same time, like a child who dreads disappointing his parents, he fears becoming a ''bad boy." ''I am a soldier and soldier is not bad if he is killing," Agu says. ''I am telling this to myself because soldier is supposed to be killing, killing, killing. So if I am killing, then I am only doing what is right." An American of Nigerian descent, Iweala graphically details Agu's atrocities, but never fails to relay, with aching poetry, the most shocking act of all -- an unwilling child plunged into the physic

A Stunningly Horrific War Story Told by a Child Soldier

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

A young boy named Strika pulls another young boy named Agu out of his hiding place and into the middle of a senseless civil war in an unnamed African country. Agu is dragged before the Commandant, the ruthless leader of a troop of soldiers, and given a choice: join or die on the spot. It is a devil's bargain, since the price of Agu's joining and saving his own life is to hack another person to death with a machete. "I am not a bad boy," Agu reasons to himself (in so many words) over the killing. "I am a soldier now, and soldiers kill, so I am only doing a soldier's job and not being a bad boy." Uzodinma Iweala's stunning first novel tells the story of Agu's indoctrination into an adult world of civil warfare, a world of fear and hardship and stomach-churning violence. More significant, Agu enters a world of loss - separation and possibly death of his family, loss of his faith, and loss of his childlike (and sexual) innocence. If he survives the war, regardless of its outcome, he is clearly scarred for life psychologically as well as physically. Two aspects of BEASTS OF NO NATION contribute to its narrative power. The first is Iweala's ability to convey a sense of blind irrationality. He gives us no sense of what country we are reading about, we have no idea who the competing factions are or what they are fighting for (or against) -- we don't even know into which side Agu has been conscripted. At the same time, Iweala offers no plan of attack, no pattern to the Commandant's movements, and no military objective being sought. The Commandant and his troop are little better than the scurrying ants to which Agu constantly refers, skittering about the countryside pillaging and destroying whatever they find and otherwise simply fighting the enemy and their hunger and fear to stay alive. The second source of narrative power derives from the author's choice of narrator and narrative style. The entire story is rendered through Agu's eyes and voice. We see the civil war through a child's uncomprehending eyes and we are as confused about the issues and reasons for killing as he is. We hear the story in Agu's voice, a mixture of childlike innocence and a broken, pidgin English that makes us see events and feel emotions through a child's limited vocabulary and his struggles to articulate the utter senselessness of what he is witnessing. This language may grate for some or seem like a novelistic contrivance (after all, assuming Agu really thinks and speaks in his native tongue, why must we see it translated in such mangled English from a boy who appeared to be moderately well-educated?). It is also fraught with the writerly complication of having a semi-articulate narrator who somehow has enough command of the language to summon up words like camouflage, crater, masquerade, junction, verandah, catarrh, vomit, and insubordination. In the end, despite the inhuman violence and sexual degradation he has experienced, Agu claims for himself the mantle of human

a powerful, moving and disturbing tale

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

I am not sure how to write this review. I was profoundly affected by the book. I've tried to re-edit it to convey just how special and moving it is, and words fail me. Fortunately, they did not fail the author. The author chose his words well, using them to convey the youth, innocence and intelligence of Agu. Each sentence is a gem. The character in this book is a child who has gone through hell. I understand a little through the book about how and why he became a mercenary (or rebel soldier, which was he? and is it different?) What makes a child kill for a cause he does not completely understand? This book answers both everything and nothing. Maybe the answer is survival. Or, maybe it is in the words of Agu "I am also having mother once, and she is loving me." What stikes me the most about this book is that Agu somehow keeps his true self alive, hidden in a part of himself. The author does not tell us what Agu's future will be, but, I hope that with the love and education his parents have given him, he will do well. Yes, I know that he is only a character, but to me, he is real, and I worry about his future.

Beasts of No Nation Mentions in Our Blog

Watched it? Now Read It!

Published by Ashly Moore Sheldon • December 14, 2023

Sometimes, the best literature gets delivered to our television screen before we've had the chance to read it. But even if you've already watched, it's never too late to read. Here are the books behind 26 of the best adaptations on Netflix right now.