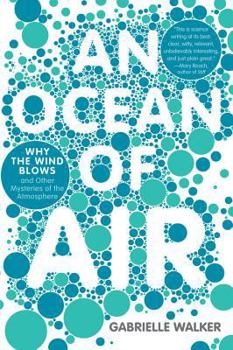

An Ocean of Air: A Natural History of the Atmosphere

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

We don't just live in the air; we live because of it. It's the most miraculous substance on earth, responsible for our food, our weather, our water, and our ability to hear. In this exuberant book, gifted science writer Gabrielle Walker peels back the layers of our atmosphere with the stories of the people who uncovered its secrets: * A flamboyant Renaissance Italian discovers how heavy our air really is: The air filling Carnegie Hall, for example, weighs seventy thousand pounds. * A one-eyed barnstorming pilot finds a set of winds that constantly blow five miles above our heads. * An impoverished American farmer figures out why hurricanes move in a circle by carving equations with his pitchfork on a barn door. * A well-meaning inventor nearly destroys the ozone layer. * A reclusive mathematical genius predicts, thirty years before he's proved right, that the sky contains a layer of floating metal fed by the glowing tails of shooting stars.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:015603414X

ISBN13:9780156034142

Release Date:August 2008

Publisher:Houghton Mifflin

Length:288 Pages

Weight:0.70 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 5.2" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

An Ocean of Air

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

A copy of An Ocean of Air should be on every library bookshelf in the world. I found this text both immensely informative and extremely interesting. Quite a number of times, I jumped up, put the book down, and went to find someone to tell about an remarkable fact or a story about a particular scientist that I thought was amusing. The book is set up in chronological order, exploring the various issues surrounding air. It starts off with the presumptions about air that our ancestors had about the substance. Then, it begins looking at the various individuals who were courageous, curious, and sometimes just plain mad enough to ask questions and seek answers. The stories progress throughout touching on a variety of associated topics from chemical composition of air and the ozone layer to carbonation and space flight. Apart from the historical and scientific usefulness of this book, I also want to note the humanizing aspect of the various scientists. Often when we picture scientists, we assume that they sit in their laboratory using their great intellect to uncover scientific discoveries. We don't often think about the sacrifices of these individuals or that often such discoveries have not always been popular. Moreover, often the most interesting successful experiences were those that went horribly wrong.

An Ocean of Air by Gabrielle Walker

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Each and every day the people of the world go about their daily activities: going to school, going to work, going to help someone; all with little idea of the great ocean of air above them that has trillions of molecules constantly performing crucial reactions - much like the population below - with the aim of keeping this planet (and its people) healthy and alive. An Ocean of Air by Gabrielle Walker is an excellent 235 page book that teaches you everything you could ever want to know about our atmosphere, its many layers, and the very air we are constantly breathing. Part science book, part history book; An Ocean of Air provides a whole semester's worth of knowledge and learning in just a single volume. Walker is an award-winning scientist with a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Cambridge University. As well as having served as climate-change editor for Nature and features editor for New Scientist, she is a visiting professor at Princeton University and has presented many programs for BBC Radio. In An Ocean of Air, she breaks down the atmosphere into its components, explaining each in detail and in clear layman's language, making it easy to understand for any reader. Along with the science, she also goes into the history of when this air molecule or atmospheric layer was discovered, how and by whom. Apart from learning the makeup of our atmosphere, the reader is also learning of great scientists and inventors of the past who were able to discover so much about something that is essentially invisible. The book is split into two parts. The first part, "Comfort Blanket," explains what the air we breath consists of; the fascinating evolution of oxygen and why we cannot live without it, but at the same time it leads to our inevitable deaths; and how wind is formed and develops into the fierce and destructive hurricanes and tornadoes around the world. The second part, "Sheltering Sky," is where Walker explains the various levels of our atmosphere, their history and discovery, from stratosphere to ionosphere - which is constantly being bombarded with radiation from the sun, but causes a reaction that protects the complex life below. It is here that Walker launches into the crux of the book, explaining the history of global warming from the invention of CFCs and the depletion of the ozone layer, to our present which is just beginning to look towards and understand the possibility of a doomed future. Just as anyone can be amazed at the complexity of the human body and how it keeps living and moving with the millions of different processes and reactions taking place constantly, our atmosphere is seemingly just as complex and in some ways fragile. Walker keenly points out that while carbon dioxide levels have spiked in Earth's history, they are now at a level never recorded before, and continuously increasing. Her intent is to inform and educate readers on what is happening to the atmosphere, and therefore the world, and with a further reading section

An Absolutely Fascinating Adventure, Not To Be Missed

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

I will say this right at the outset: This is one of the best books about a scientific topic, written for a popular audience, that I have ever read (and, believe me, I've read a lot of them). If there is such a thing as a genuine "page-turner" in the field of popular science, "An Ocean of Air" certainly qualifies to be in such a category. I can understand why Gabrielle Walker is advertised as an award-winning science writer. If I offered an award for fine writing, especially about a subject as complex as the earth's atmosphere, she would top my list of potential recipients. In my considered opinion (and thankfully!), it just goes to prove that being an "academic" and possessing a Ph.D. (which she has) does not condemn one to write books forever as one writes a doctoral dissertation (which tend to be very stilted and hopelessly boring). Creative-writing instructors have always told me that the first sentence and paragraph of a book are most important. They are the "hook" that grabs the reader and propels him or her forward onto page two, then page three, then page four, and so on, until the reader reaches the last page, excited but exhausted, forced to exhale a lung's-worth of air, declaring "what a wild ride!" Walker's book provided that experience for me, and I am not exaggerating. The story opens twenty miles above New Mexico with Joe Kittinger "hanging in the sky." It is the 16th of August in 1960. (I had just graduated from college.) Then, "For eleven minutes he remained there, poised in an open gondola that twisted slowly beneath a vast helium balloon." But, "Far below, where Earth's surface curved away to the horizon, a glowing blue halo stood out against the blackness of space." Then, on the next page we are informed, Kittinger "took a single breath of pure oxygen from within his tightly sealed helmet . . . And then he jumped." Now, we're talking twenty miles up in the air here! The highest I've ever been is around eight miles up, courtesy of a small private jet taking me to Colorado in 2005 for a philosophy conference. I was nervous during that hours-long journey because I have a real problem with heights. So, I was immediately "hooked," as they say, by Walker's opening paragraphs. I could visualize exactly what was taking place and how Kittinger must have felt. Finally the author tells us: "Captain Joseph W. Kittinger Jr. of the U.S. Air Force is the man who fell to Earth and lived. Nobody has ever managed to emulate his feat." The author's point in telling this little anecdote is to illustrate for us something important about the "ocean" of air above us and around us. As Walker says: ". . .[T]he message from Kittinger's flight, and from every one of the pioneers who have sought to understand our atmosphere" is, "We don't just live 'in' the air. We live 'because' of it." This anecdote, by the way, is told in the Prologue to the book. The reader hasn't even begun Chapter One yet. But Walker has, indeed, provided the "hook" that wil

How We Came to Understand the Air Around Us

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

If we have a bottle that has no liquid in it, or a box that has had all objects removed from it, we will say that the bottle or the box is empty. The idea that there is nothing there but nothingness is one that goes far back, and it is only common sense: you can't see or feel anything there, so there is nothing there. Science, for all its common-sense methods, might be seen as an attack on common sense; the Earth is not flat, for instance, and the Sun does not go around it (You can just see it! It's just common sense!) And that bottle and box are not empty, but full of air. That the air is something of infinite complexity (rather than being some manifestation of nothingness) was a revelation that was centuries in coming, but the way it happened is delightfully told in _An Ocean of Air: Why the Wind Blows and Other Mysteries of the Atmosphere_ (Harcourt) by Gabrielle Walker. Chapters here detail the attack of science upon different aspects of the air, like its molecular composition, the drive of the winds, the protective nature of the ozone layer, jet streams, and the effects of humans upon it. There is one example after another of how science has harnessed observation, speculation, experiment, and eventual theories to come to an understanding that, as Walker says, "We don't just live _in_ the air. We live _because_ of it." And this is not just because we need it to breathe. Walker starts with Galileo and his associate Torricelli, who had the heretical idea that vacuums existed (the church said they didn't). Galileo's calculations from clever experiments showed with good accuracy that air weighed one four-hundredth as much as water. This does not sound like much, but Walker points out that the air inside Carnegie Hall weighs seventy thousand pounds. But if air is not nothing and is made of something, what is it made of? For us animals, the important component for our breathing is oxygen, which was discovered by the combined efforts of Joseph Priestley in England and Antoine Lavoisier in France. The forgotten Scottish genius Joseph Black in 1754 was the first to isolate carbon dioxide, but he performed a huge number of experiments in different realms. He hardly published anything about them, writes Walker: "He didn't want to be the first, nor did he want to be famous; he simply wanted to _know_." The Irishman John Tyndall was a scientific showman; "He choreographed his lectures as for a Broadway show," packing houses so that the masses might share in scientific insight. Around 1860 he showed how important carbon dioxide was in soaking up warmth from the Sun, the beginning of our understanding of the Greenhouse Effect. Lieutenant Matthew Maury was no scientific genius, but he thought he was. He compiled tables and charts of air movement and air pressure around the world, but his wild explanations for them included thundering justifications from the Old Testament. It took a real genius, the West Virginian William Ferrel, to make

THE science book of the year!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

With all the talk about the effects of global warming on our atmosphere, we finally have a book that explains what the atmosphere actually is and what each layer (and there are lots of them!) does to protect us. As entertaining-- and fascinating-- as it is informative, this "natural history of air" is a must read for anyone who wants to join or simply understand the debate. Plus, Dr. Walker writes like a dream. She is the college (or high school) science teacher we all wish we had.