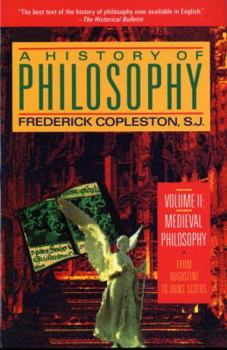

A History of Philosophy, Vol. 2: Medieval Philosophy - From Augustine to Duns Scotus

(Book #2 in the A History of Philosophy Series)

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Conceived originally as a serious presentation of the development of philosophy for Catholic seminary students, Frederick Copleston's nine-volume A History Of Philosophy has journeyed far beyond the modest purpose of its author to universal acclaim as the best history of philosophy in English. Copleston, an Oxford Jesuit of immense erudition who once tangled with A.J. Ayer in a fabled debate about the existence of God and the possibility of metaphysics,...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:038546844X

ISBN13:9780385468442

Release Date:March 1993

Publisher:Image

Length:624 Pages

Weight:1.20 lbs.

Dimensions:8.8" x 1.8" x 5.9"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

A Good Comprehensive History of Philosophy During a Thusand Years

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Father Copleston, S.J. wrote a readable account of an important era in intellectual history. Father Copleston's book is well organized and well written. He is clear that the phrase Middle Ages is misguiding. The approximate era of A HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY, VOLUME 2:MEDIEVAL PHILOSOPHY deals with approximately a thousand years (c.500 AD-1500 AD). This time frame can be divided by the Dark Ages, the Early Middle Ages or Frankish history, a Second Dark Ages, the High Middle Ages, etc. Father Copleston begins his study with the Partistic Period (Ancient Western Civilization thinking) and the impact of St. Augustine (446-520) and his great book titled THE CITY OF GOD. Chapters one through ten give the reader a comprehensive examination of ideas and European thought at a time when learning could have very well disappeared in Western Europe. Father Copleston includes some of the important figures in the Patristic Era such as Isodore (570-636), Boethius (480-524)Cassoidorus (577-665), etc. Father Copleston does a credible job in describing what is known as the Carolingian Renaissance. He mentions the valuable contributions of Alcuin (730-804) and Eriugena (815-877). The fact that Alcuin established a school at Aachen and developed bookhand as the format for handwritten books and study materials is invaluable in the teaching and learning for posterity. Eruigena was probably the first speculative philosopher in Western Europe since the disintegration of the Ancient Roman Empire. His work cannot be overestimated. Father Copleston deals with the problems of "Universals" in the early Medieval schools. He also explains the debate between the Nominalists and the Realists. Father Copleston's examination of the Medieval curriculum is useful. Undergraduate students studied the Trivium (Grammar, Rhetoric, and Logic). Students were taught to read well, to think, to speak well, and the write well. Once these students mastered this curriculum, they could study the Quadrivium (Astronomy, Music, Arithmetic and Algerbra, and Plane Geometry). If these students pursued further studies, they could study Medicine, Canon Law, and Theology which was considered The Queen of the Sciences. One should note that Medieval Catholic universities were centers of intellectual activity and spirited debate which has disappeared from the record. In other words, Father Copleston undermines that the Catholic Church authorities somehow undermined serious learning and thinking when in fact they encouraged it. Father Copleston begins his treatment of Scholasticism with St. Anselm (1033-1109) whose PROLOGIAN was a serious study that at some point the Catholic Faith had to be reasonable to be accepted. This study began the fruitful development of Scholastic Philosophy. Mention should be made of Peter Abelard (1079-1142) whose SIC ET NON caused scandal until scholars realized that this was a "how to" book on solving complex philosophical and theological problems. One should

The Philosophy that Time Forgot

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Anyone acquainted with the history of philosophy knows there is a tendency to treat Medieval philosophy as a low point between the grandeur of Greece and the radiant glow of Descartes, who salvaged philosophy from the dim ruminations of Christian theology. This theme is given notable currency in popular histories like Russell's _History of Western Philosophy_, Durant's _The Story of Philosophy_, and Gottlieb's more recent _Dream of Reason_. While these books might pay homage to Aquinas as a synthesizer of Aristotle and Catholicism, his eminent contemporaries hardly merit a sentence. Supposedly, real philosophy did not begin in earnest until it was reawakened by the "kiss of Descartes." Here Frederick Copleston, a great Jesuit scholar, seeks to remedy the damage by recreating the rich philosophical tapestry of Medievalism, a time in which philosophy hardly slept, but was full of energy and acerbic controversy. While Christianity was definitely the philosophical template that all Medievalists began with, there was still an enormous range of conflict and disputation. Just as there is not a single issue that ensnares modern philosophy, the Medievalists were engrossed with a whole range of issues -- epistemology, politics, rationalism, and so on. A prickly controversy that the Medievalists dwelt on was the "problem of universals", an enigma that dates back to Plato and Aristotle, who each took opposing sides to the problem. On the surface the problem of universals might not seem like a problem at all, and indeed most people do not recognize it as such until they encounter it in Philosophy 101. While different formulations can be given to the problem the most succint way of presenting it is as follows: what, if anything, in extramental reality corresponds to the universal concept in the human mind? In other words, our minds (or brains) can only produce thoughts and conepts, but the world (extramental reality) is made up of particular, individual things. So what is the relationship between our thoughts and individual things, between between the intramental concept and the extramental reality? For instance, when the scientist expresses his knowledge of things he does so in abstract and universal terms, he does not make a statement about a particular atom, but atoms in general, and if the universal term has no foundation in extramental reality, his science is a social construction. This is one of the vexing issues the Medievalists tried to confront and resolve and fortunately progress was made in the area. The crude, "exaggerated" realism of Christian Platonists, like Saint Anslem, eventually gave way to the more moderate realism of Aquinas. The extreme realists were under the impression that class-names for genera and species -- things like trees, elms, felines, cats, dogs, etc -- had a real existence -- the mental concept was indentical to extramental reality. There is a unitary nature between our minds and the world, terms had a real existence, and wer

The finest history of philosophy ever written

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Warning: this book is not for the faint-of-heart -- or faint-of-mind! Staggeringly detailed, Copleston's history of philosophy is one of the masterworks of twentieth century scholarship, but should only be assayed by those who have done their basic work in philosophy already. As a Jesuit, this volume is perhaps the closest to Copleston's heart, given that it covers Catholic philosophy from Augustine to Thomas Aquinas (who Copleston believes is his own truest philosopher), as well as a few odds and ends of medieval philosophy. The sections on Augustine and Aquinas are still required reading for anybody wanting to understand the attempt to reconcile philosophy and theology, the primary intellectual debate of the middle ages in Europe. For many readers, the debate simply won't matter any longer, but anybody wishing to understand the medieval mind absolutely needs to read this book. Yes, your head may swim in keeping the arguments over what now seems to many to be inconsequential trivia, but the terms and arguments that Aquinas defined set the ground for many unresolved arguments to follow.

Some caveats

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

The readers were originally seminarians. Often a critical word or phrase is rendered in Latin or Greek. You can work around that by treating the word as a symbol for an idea otherwise explicated, but sometimes in this book (less so in the prior ones) a critical eplanation or reference is entirely in Latin. The book, as is true with all of the others, is well worth the work involved in studying it. It is neither an in depth analysis of everything, nor a beginner's text. Excellent for college students and particularly philosophy students who have finished the survey courses.