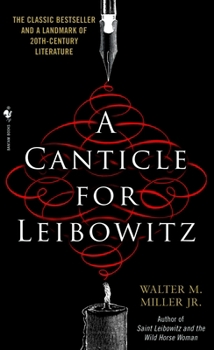

Book Overview

In the depths of the Utah desert, long after the Flame Deluge has scoured the earth clean, a monk of the Order of Saint Leibowitz has made a miraculous discovery: holy relics from the life of the great saint himself, including the blessed blueprint, the sacred shopping list, and the hallowed shrine of the Fallout Shelter. In a terrifying age of darkness and decay, these artifacts could be the keys to mankind's salvation. But as the mystery at the core of this groundbreaking novel unfolds, it is the search itself--for meaning, for truth, for love--that offers hope for humanity's rebirth from the ashes.

Format:Mass Market Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:B001UC3HNE

ISBN13:9780553273816

Release Date:June 1984

Publisher:Spectra Books

Length:368 Pages

Weight:0.44 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 4.3" x 6.9"

Customer Reviews

10 ratings

Worth The Read

Published by Nick , 9 months ago

Walter Miller's Masterpiece

Makes a great sequel to Farenheit 451

Published by Michael , 2 years ago

Even though it was not meant to be, it makes a great sequel to Farenheit 451. In fact, I liked it better.

Not at all what I expected

Published by Thorin son of Thrain , 3 years ago

I had no idea what to expect going in on this book, I will say that it is one of the stranger books I’ve read. But it is outstanding. The characters and dialogue are excellent and the dilemmas that they face are thought provoking. Will likely re-read.

Great book, one of my favorites

Published by Gnu , 4 years ago

Though the book was written at the beginning of the atomic age, it is uncannily relevant in today's technical and political scene.

Really important book!

Published by Ilana G , 5 years ago

Not gonna lie, this was a bit of a tough read. However, the message is so important so if you have the time/energy I highly recommend this book!

The Greatest Science fiction of the last 75 years

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

I would love to see this book made into a movie

Miller's highly personal struggle with religion and science

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Walter Miller's only major novel is not simply a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel but also a multi-layered meditation on the conflict between knowledge and morality. Six hundred years after a nuclear holocaust, an abbey of Catholic monks survives during a new Dark Ages and preserves the little that remains of the world's scientific knowledge. The monks also seek evidence concerning the existence of Leibowitz, their alleged founder (who, the reader soon realizes, is a Jewish scientist who appears to have been part of the nuclear industrial complex of the 1960s). The second part fast-forwards another six hundred years, to the onset of a new Renaissance; a final section again skips yet another six hundred years, to the dawn of a second Space Age--complete, once again, with nuclear weapons. The only character who appears in all three sections is the Wandering Jew--borrowed from the anti-Semitic legend of a man who mocked Jesus on the way to the crucifixion and who was condemned to a vagrant life on earth until Judgment Day. Miller resurrects this European slander and sanitizes him as a curmudgeonly hermit, a voice of reason in a desert wilderness, an observer to humankind's repeated stupidities, a friend to the monks and abbots, the ghost of Leibowitz (perhaps)--and even the voice of Miller himself. Throughout "Canticle," Miller's search for religious faith clashes with his respect for scientific rationalism. For Miller, Lucifer is not a fallen angel but technological discovery unencumbered by a moral compass; "Lucifer is fallen" becomes the code phrase the future Church uses to indicate the imminent threat of a second nuclear holocaust. The ability of humankind to abuse learning for evil purposes, to continually expel itself from the Garden of Eden, perplexes and haunts the author: "The closer men came to perfecting for themselves a paradise, the more impatient they seemed to become with it, and with themselves as well." Some readers might be turned off by the book's religious undercurrent, but that would be to mistake fiction for a sermon. The work is certainly infused with the author's Catholicism, but its philosophy is far too ambiguous to be read like a homily. This is no "Battlefield Earth." Instead, it is Miller's highly personal act of atonement; he acknowledged later in life that his fictional monastery was first subconsciously, then purposefully modeled on the ancient Benedictine Monastery at Monte Cassino, which, as a World War II pilot, he bombed to smithereens. (An historical aside: most of the major Greco-Roman scientific and mathematical texts were preserved for posterity by Arabic scholars--not by medieval Catholic monks. But this is fiction, and it's not clear whether Miller is trying to replicate Church history as it was or as he felt it should have been.) In many ways, Miller's Catholicism is as conflicted in the book as it was in his own life. He changed religious beliefs several times; in the 1980s, he immersed himself

I need a 10-star rating for this book.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

There's no point in even trying to describe A Canticle for Leibowitz. It's pure Genius-with-a-capital-G. If you're literate and don't need all the whiz-bang crap that usually populates sci fi (I don't even think I would consider this sci fi, it's so... WAY beyond the norm); that is, if you can think independently, Read This Book. Don't worry about all the latin... he doesn't translate most of it but you can imply meaning from context.So... I can't describe it, but here are some reasons why I consider Canticle pure Genius.Canticle :1. Offers an entirely classical and yet revolutionary reading of history.2. Is a darn good story.3. Is purely intellectual, working to excite thought and reason and possibility rather than visual senses or innovations.4. Gives credit to Christianity for preserving literacy over the centuries, a fact that is usually overlooked.5. Respects religion; most sci fi novels either disdain religious people, lampoon them, or write them off as annoying or dangerous quacks. This one treats them with the respect they deserve.6. Is, perhaps, an incredible act of penance by the author (read the "about the author" when you finish).7. Addresses all the serious questions in life: suicide, war, pacifism, what the role of religion in society is... the list is endless. 8. Is the epitome of intertextuality. It doesn't mention any specific works (though the Inferno is quoted), but it draws heavily (purposefully) from world and biblical history... not only so that it may enlighten us about the current text (the arrow usually goes that way), but rather to prompt us to view PREVIOUS texts in a totally different way.9. Asks the question: Why do we mistrust our historical sources so much?10. Hasn't dated itself a day since it was written in 1959. Not a day.11. Contains thoughts so terrible and yet beautiful it made me cry.So read it. Or abandon hope, ye who enter here.

Those who learn from the past are condemned to repeat it.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

A Canticle for Leibowitz begins when nuclear warfare (aka The Flame Deluge) destroys the vast majority of civilization. Immediately following the holocaust, a group of survivors called The Simpletons wage a full-scale pogrom and book burning campaign against surviving scientists, politicians, teachers, etc. - those they feel were responsible for the war. The new Dark Age is called The Simplification, which lasts for many hundreds of years. A former physicist named Isaac Leibowitz devotes his life to the Catholic Church after the Deluge. Leibowitz is able to persuade the Church (whom The Simpletons leave alone to a certain extent) to protect whatever written material remains. After being turned over to The Simpletons by a turncoat technician, Leibowitz is killed and considered a martyr by the church. ACfL is a story that spans nearly twelve centuries centering on the abbey seeks to canonize Leibowitz, The Albertian Order of Leibowitz. The story is broken into three sections: Fiat Homo, Fiat Lux, and Fiat Voluntas Tua.Fiat Homo is about a bumbling young monk named Brother Francis who has a squabble with The Wandering Jew, who later directs Francis to a bomb shelter which contains a few papers that may have belonged to Leibowitz himself. Fiat Lux deals with a war about to be started by powermad dictator Hannegan, who is Idi Amin-like in his stupidity. The dictator's nephew is a brilliant scientist who hasn't quite come to terms with the fact his discoveries are actually rediscoveries. Fiat Voluntas Tua shows two warring societies about to make the same mistake that nearly destroyed humanity eighteen hundred years before.In addition to writing this brilliant novel, the late Walter M. Miller Jr. was in the same bombing raid that destroyed Benedictine Abbey at Monte Casino during World War II. This event I'm certain had much to do with Miller writing ACfL. ACfL brilliantly proves how no amount of technological progress exempts us from responsibilty for our deeds. When something bad happens, be it to us or someone else, we are not to say "That's life." in order to lessen the load on ourselves. ACfL also points out how people have gone to downright atrocious extremes to reclaim Eden instead of accepting the world as it is. The closer someone comes to making paradise for themselves, the more miserable they become. In short, the problem is not technology. The problem is not God. The problem is us.

A possible post-apocalyptic scenario--highly recommended

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

"A Canticle for Leibowitz" chronicles the rebuilding of "civilization" after nuclear holocaust. It has three distinct sections, each separated by hundreds of years, centering around life at a desert monastary named in honor of a very unusual "saint". Since each section tells its own story, and could be read separately, I'm going to rate each one separately.PART ONE: FIAT HOMO (5 stars) Tipped off by a mysterious old man (could it be Saint Leibowitz himself?), a nervous novice monk discovers an underground chamber that contains some highly significant relics, for which he suffers abuse from a fearful and sadistic abbot. Eventually, he is sent on a dangerous journey to New Rome, under constant threat from primitive nomads. The ending of this section is rather chilling and ironic, much like a Flannery O'Connor short story. PART TWO: FIAT LUX (3 stars) This is the only section among the three that really is not able to stand alone as a self-contained story with a definitive ending. I suppose this could be considered the "Empire Strikes Back" of the "trilogy". The basis of this part is the mistrust that exists between religion and science, when a scholar visits the monastary to study the ancient Leibowitz documents and finds, to his astonishment, one of the monks has invented (or re-invented) the electric light. The old man reappears (remember, this is hundreds of years after the first story) as a rather significant player in this section, but, ultimately, this story is merely transitional.PART THREE: FIAT VOLUNTUAS TUA (5 stars) I wanted to give this part 6 or 7 stars, but that would be cheating. This last section is absolutely brilliant. Many hundreds of years later, the inevitable happens, proving that mankind apparently never learns from its mistakes. The very wise abbot (it is interesting how each abbot in these stories is wiser than the last) sees the handwriting on the wall and commissions a group of monastics, accompanied by the relics of Saint Leibowitz, to escape by rocket ship to a distant planet to guarantee the perpetuity of the order and, indeed, of the faith itself. Meanwhile, the abbot and a medical doctor grapple over the appropriateness of euthanasia for suffering victims of the fallout. (Any groups or classes that might be discussing the subject of mercy killing would benefit greatly by reading this section since it lays out the opposing arguments very clearly and forcefully). Although the ultimate disaster takes place, hope is still found in the most unlikely person: a mutant, two-headed woman. And so we begin again.This book takes a very positive, optimistic view of religion, while it is pessimistic about mankind in general. The stories included here work on many levels, and the book as a whole makes for an enlightening reading experience.